How Negative Space Shapes Your Photos

In photography, Negative Space refers to the empty or unoccupied areas that surround the main subject within a composition. While it may seem like “nothingness,” Negative Space plays a crucial role in shaping the overall balance, mood, and visual impact of an image. It’s the area that allows the subject — known as Positive Space — to stand out clearly and command attention.

Think of Negative Space as the breathing room in a photograph. It gives the viewer’s eye a place to rest and helps emphasize the main subject without distractions. Far from being just a background, it becomes a compositional tool that gives structure and purpose to the image.

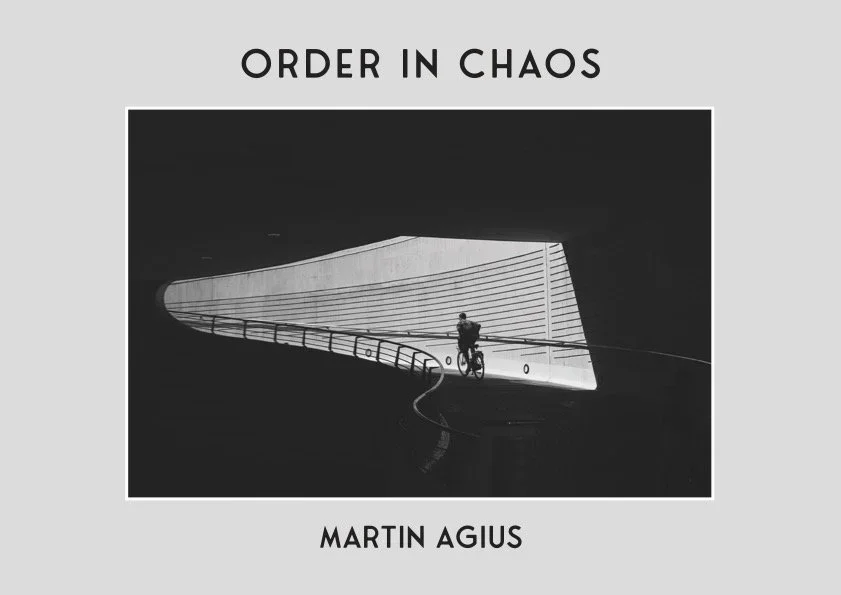

The Power of Simplicity - “Less is More”

Negative Space often aligns with the minimalist philosophy that less is more. By simplifying a scene, photographers can highlight what truly matters and eliminate visual clutter. A photograph doesn’t always need to be filled with detail to be powerful. In fact, sometimes, it’s the emptiness — the sky, a blank wall, a stretch of sea — that provides emotional depth.

When used effectively, Negative Space can convey a variety of feelings:

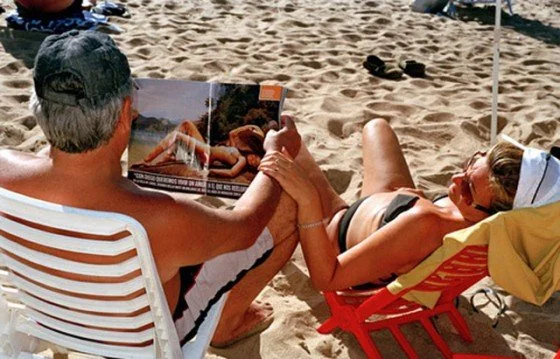

● Calmness and Serenity - by using soft tones and balanced composition

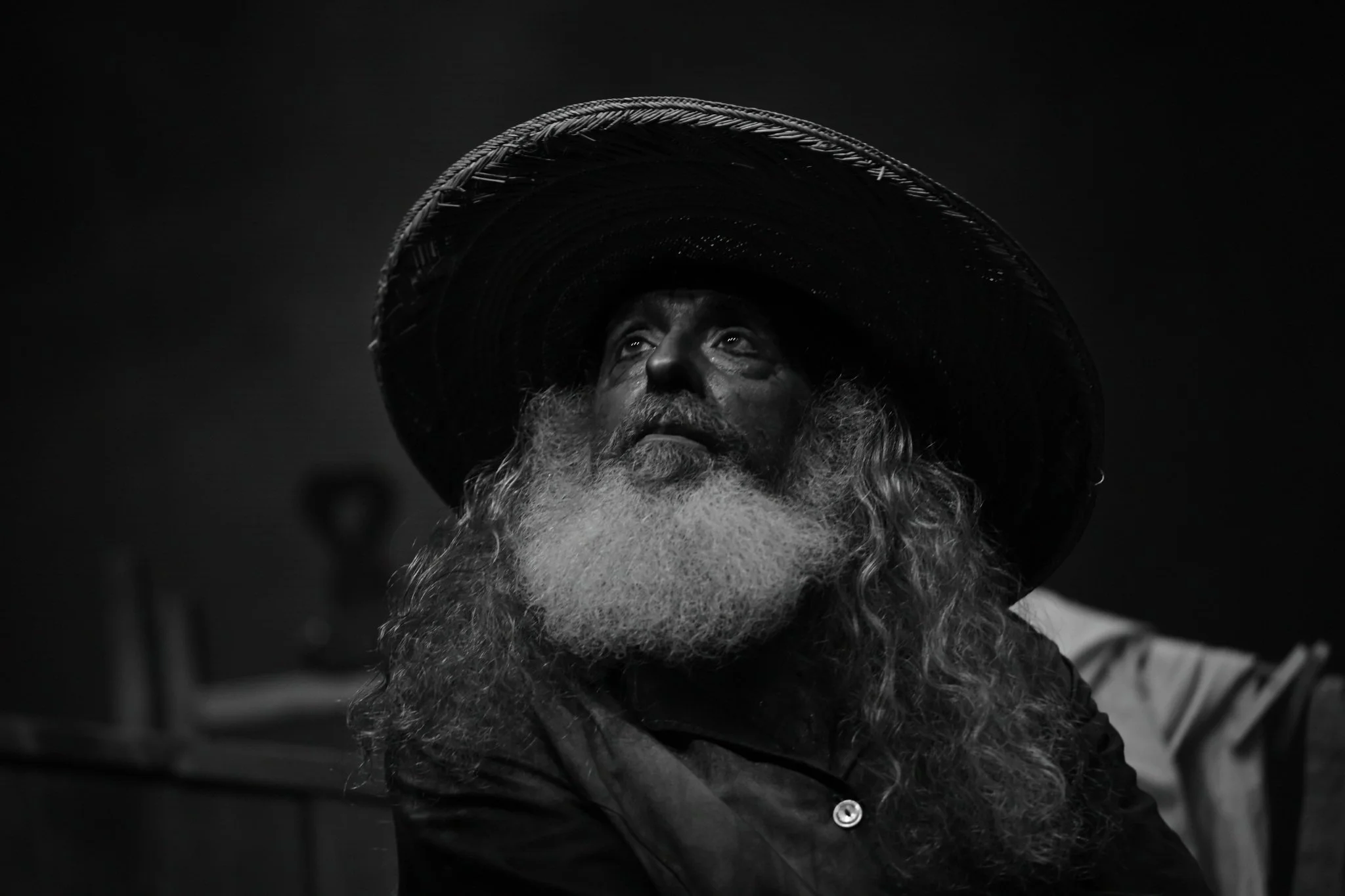

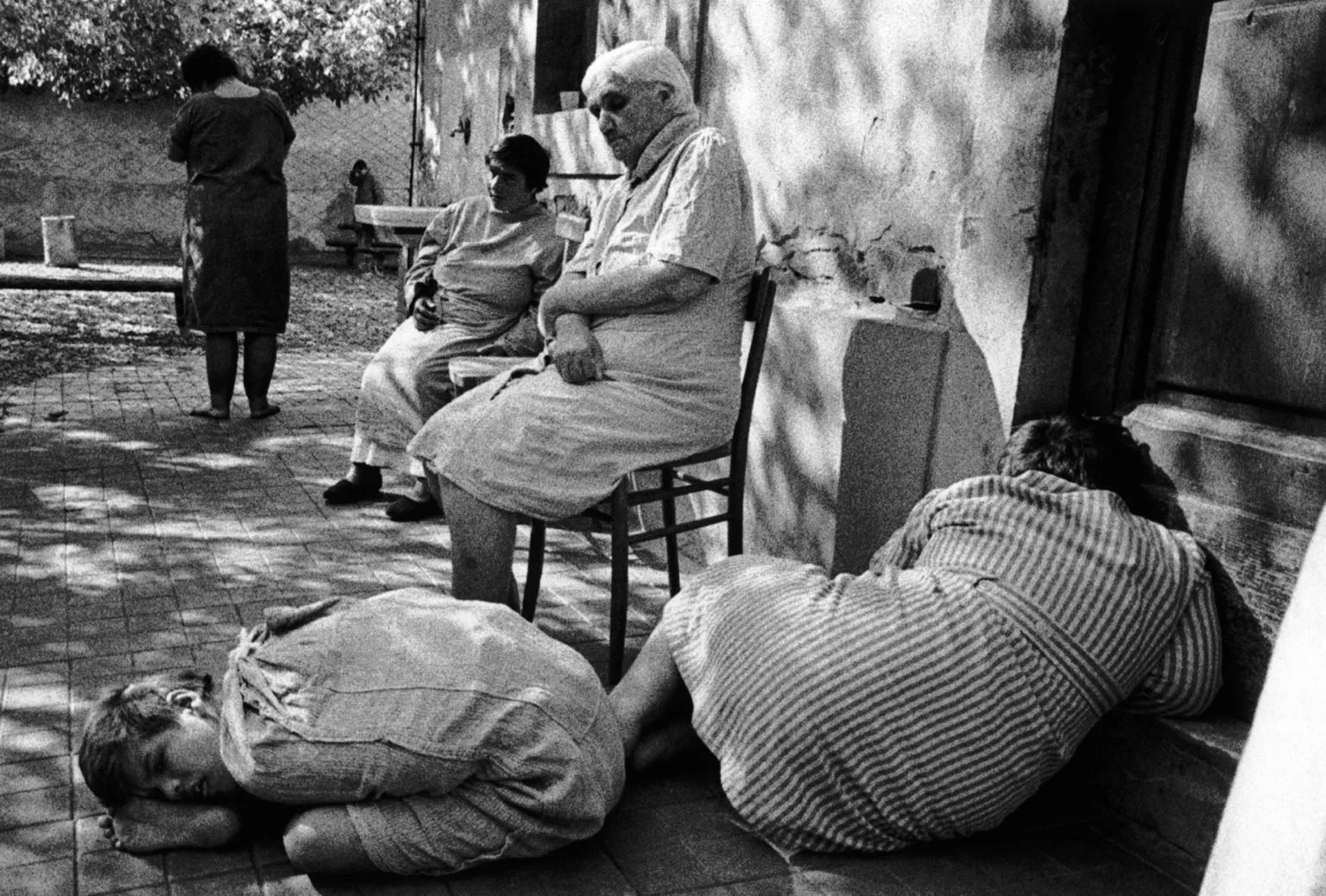

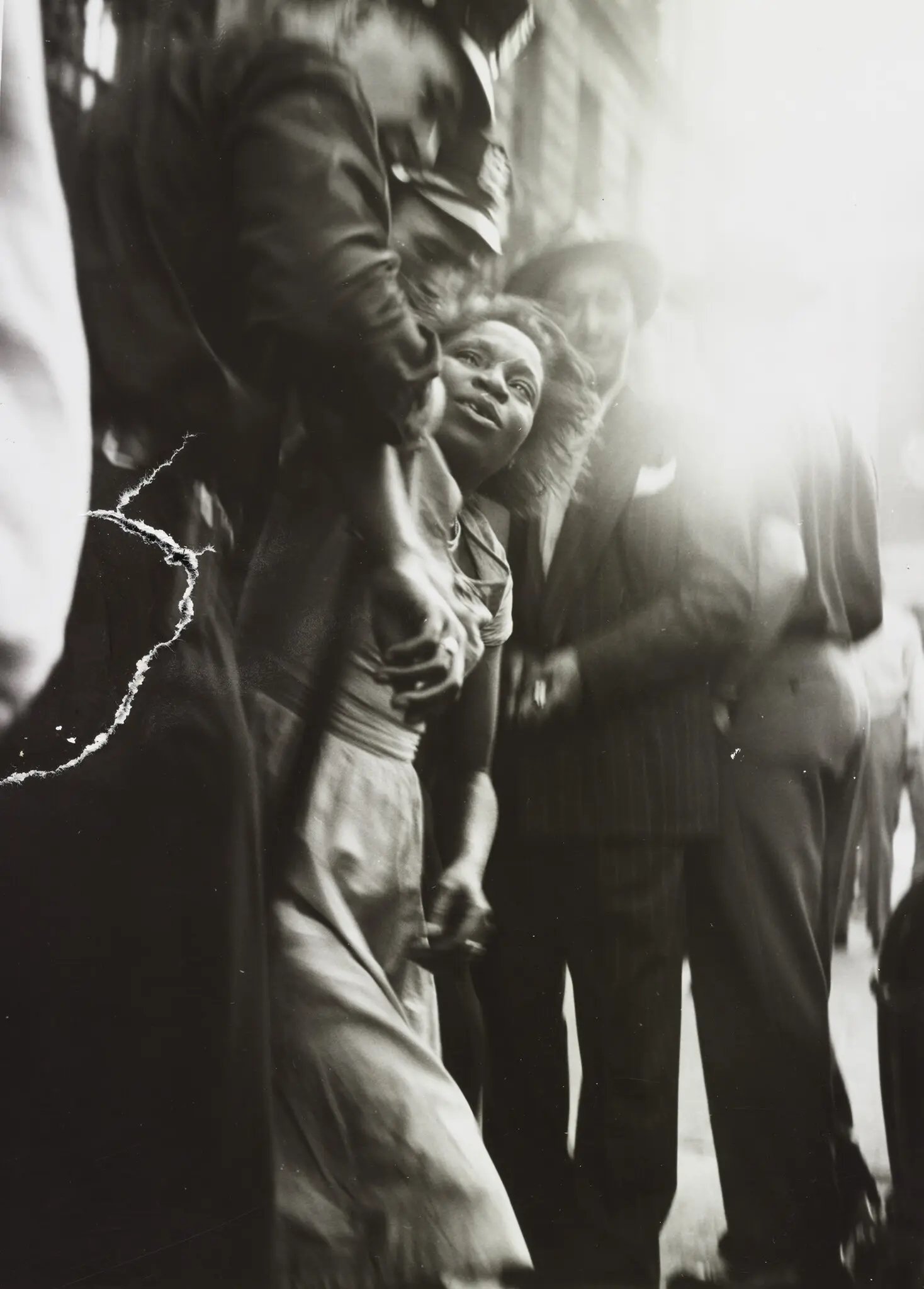

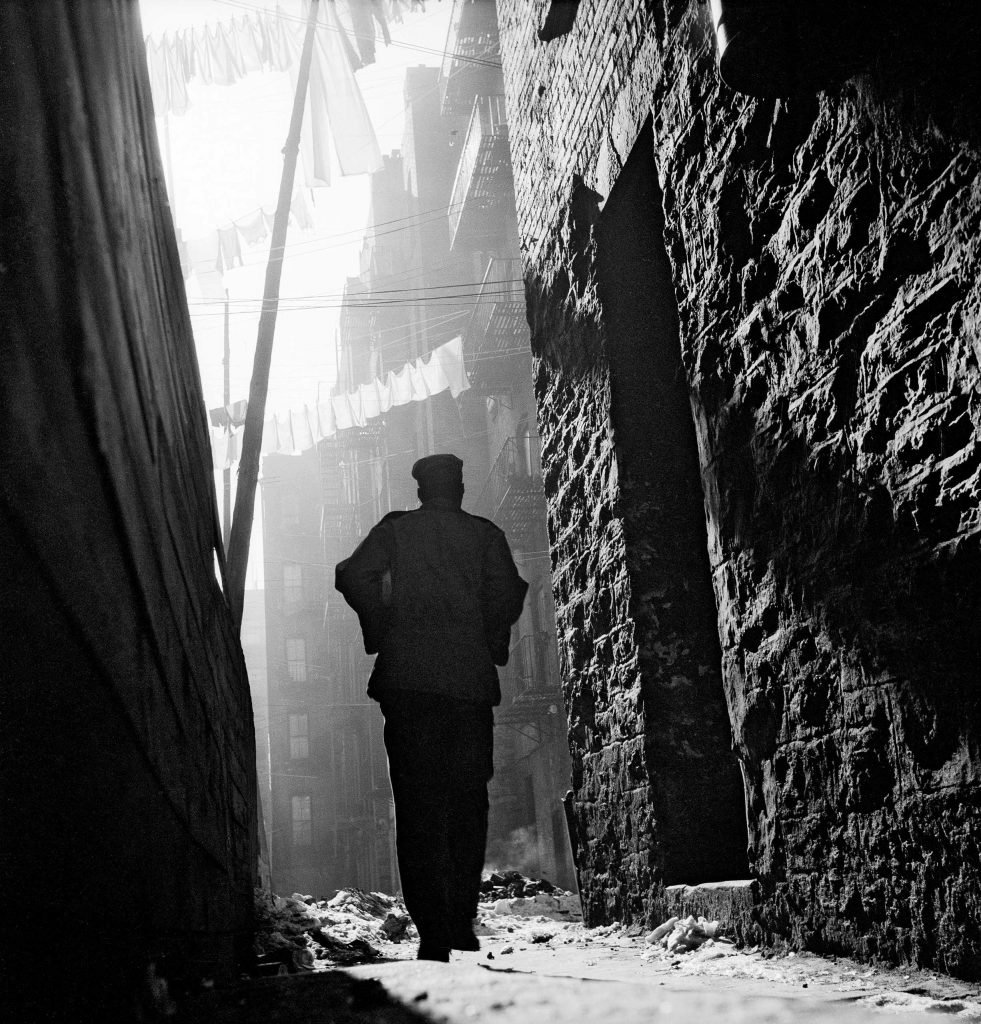

● Solitude or Isolation - through large empty areas and small subjects

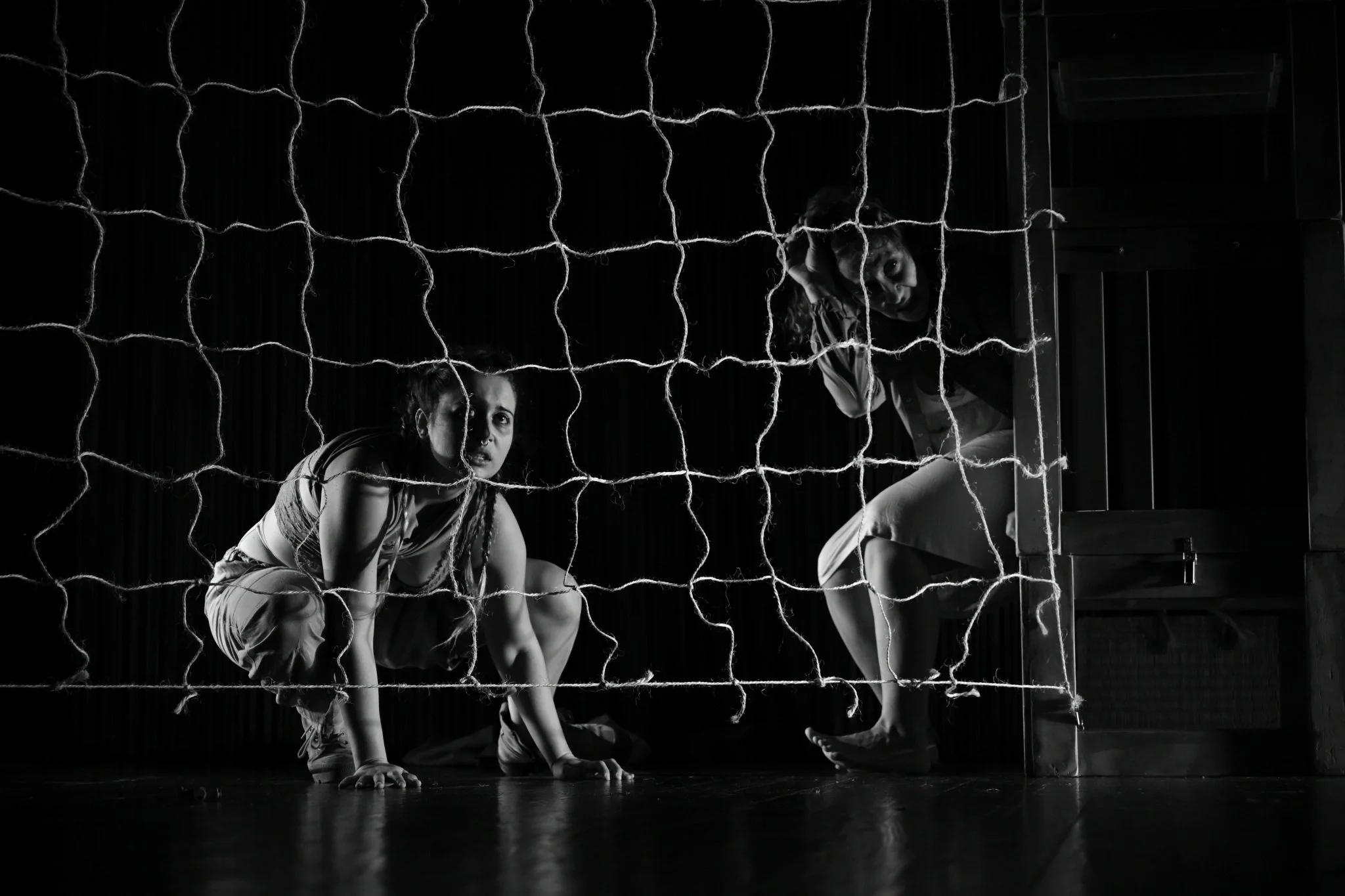

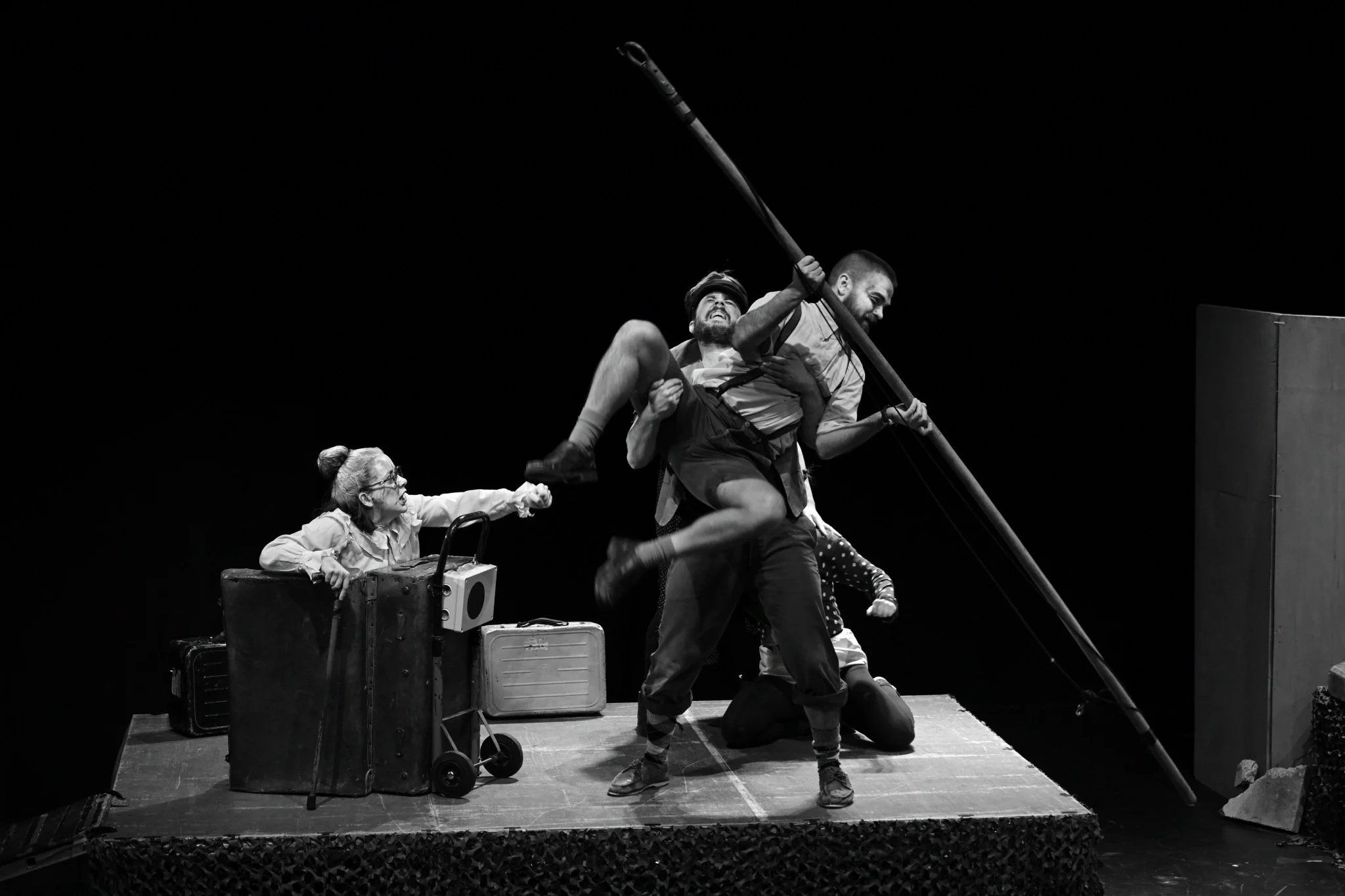

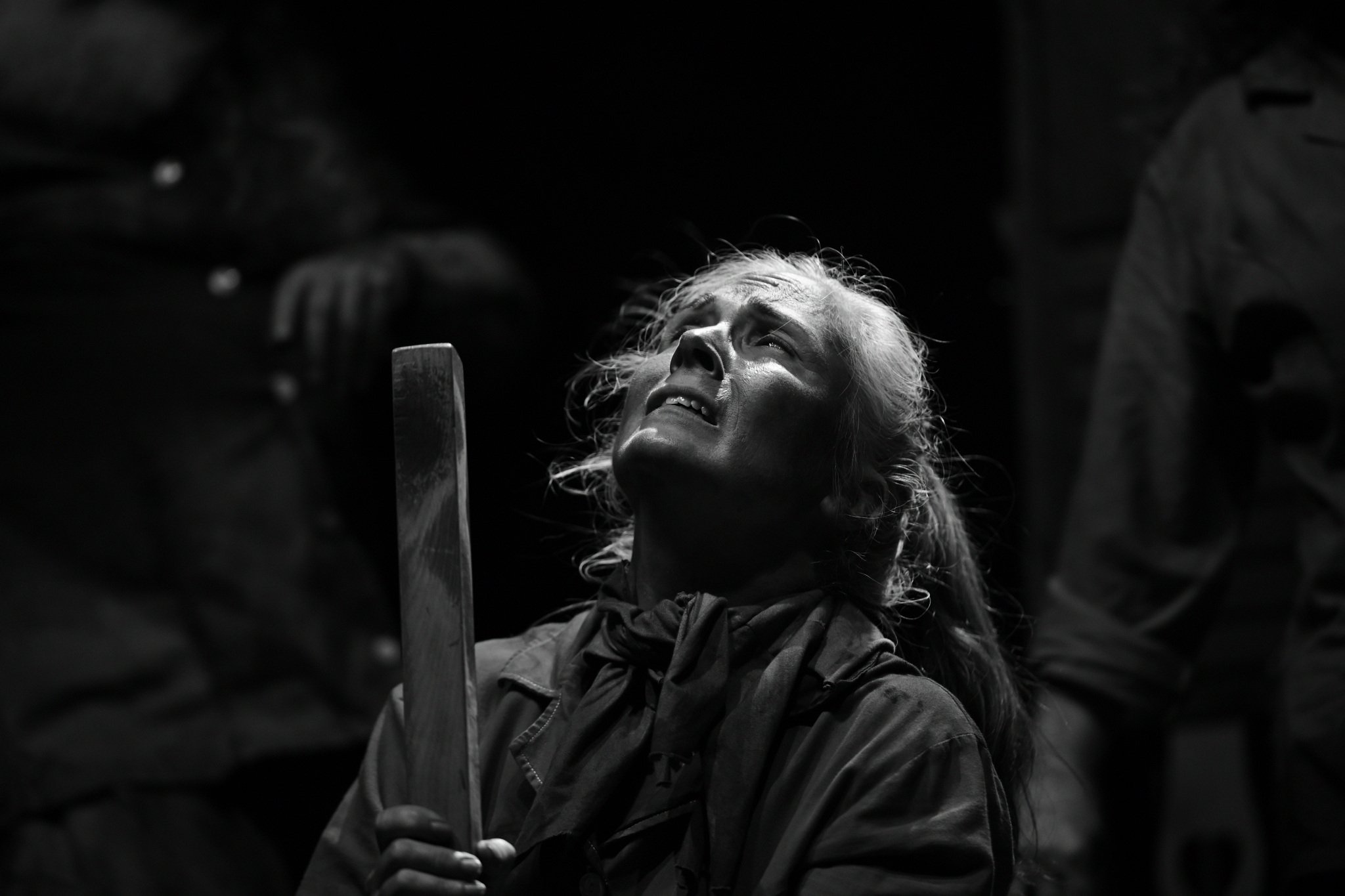

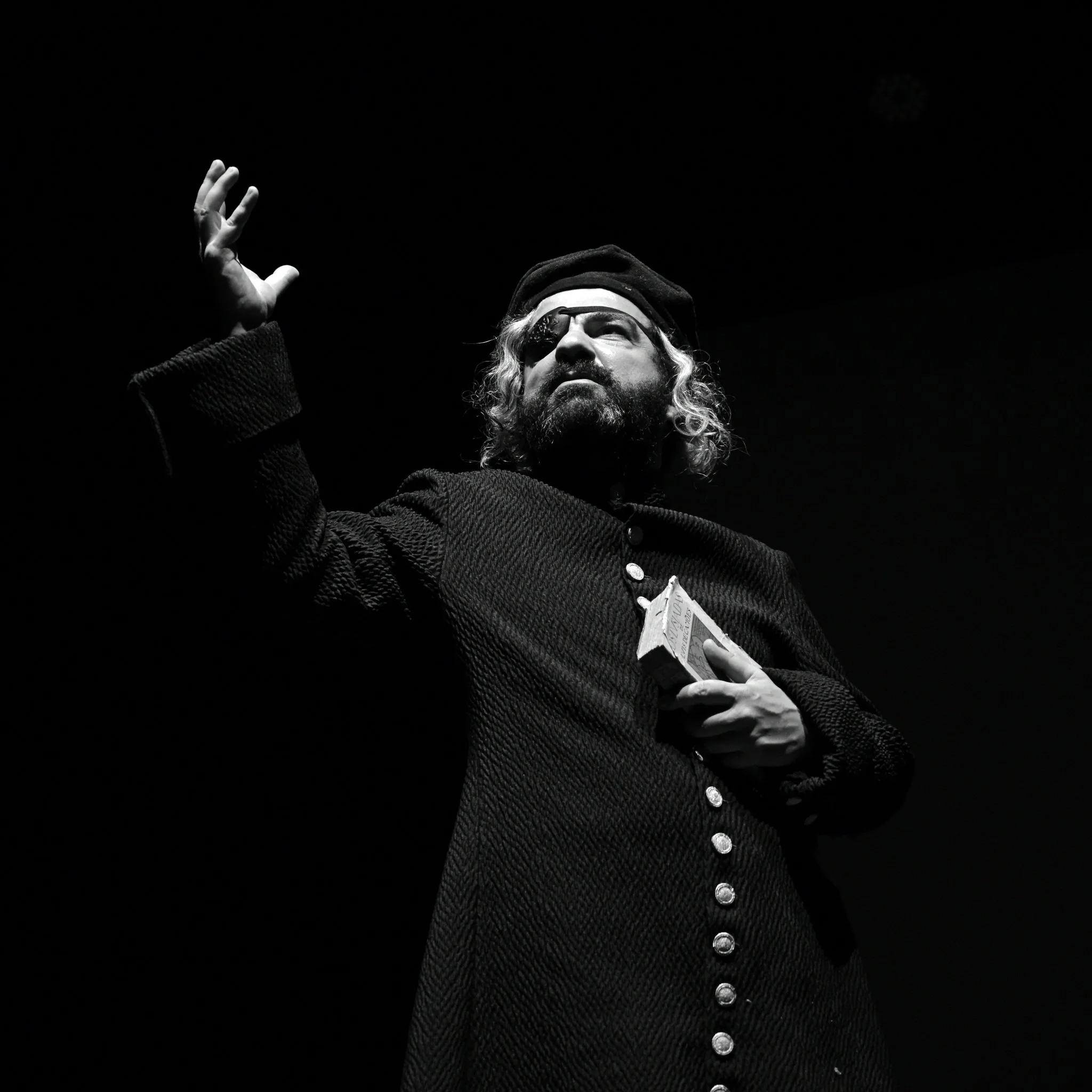

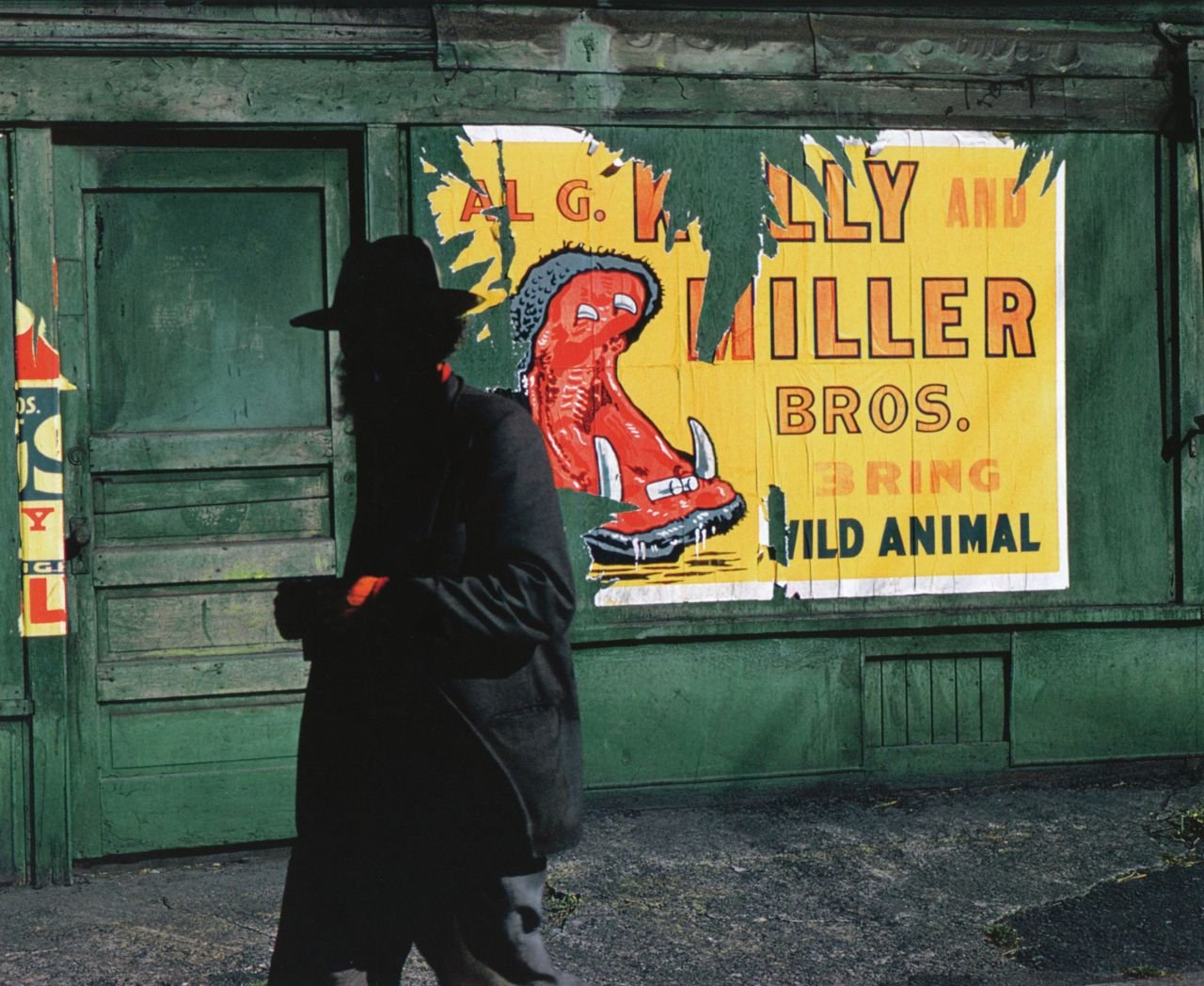

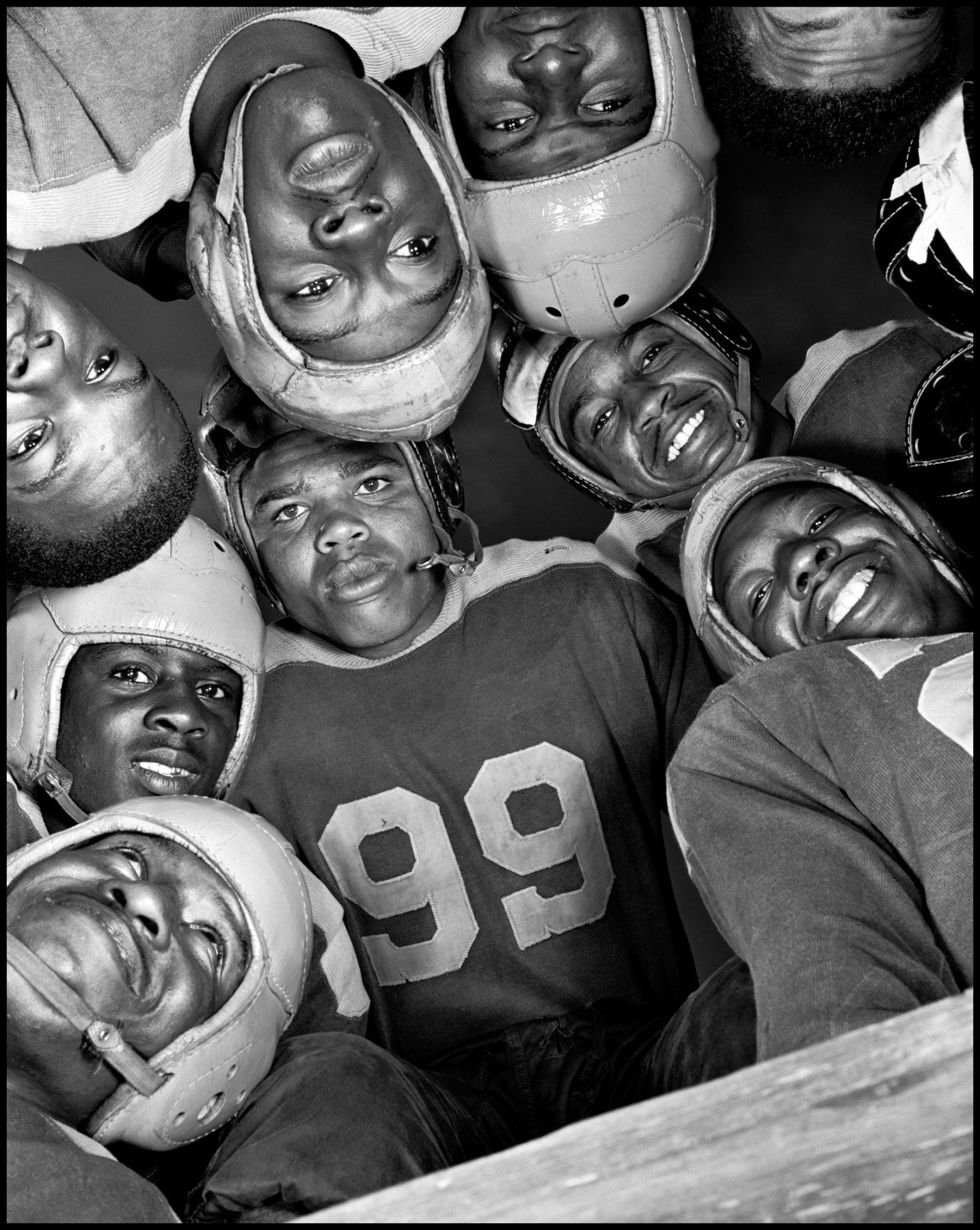

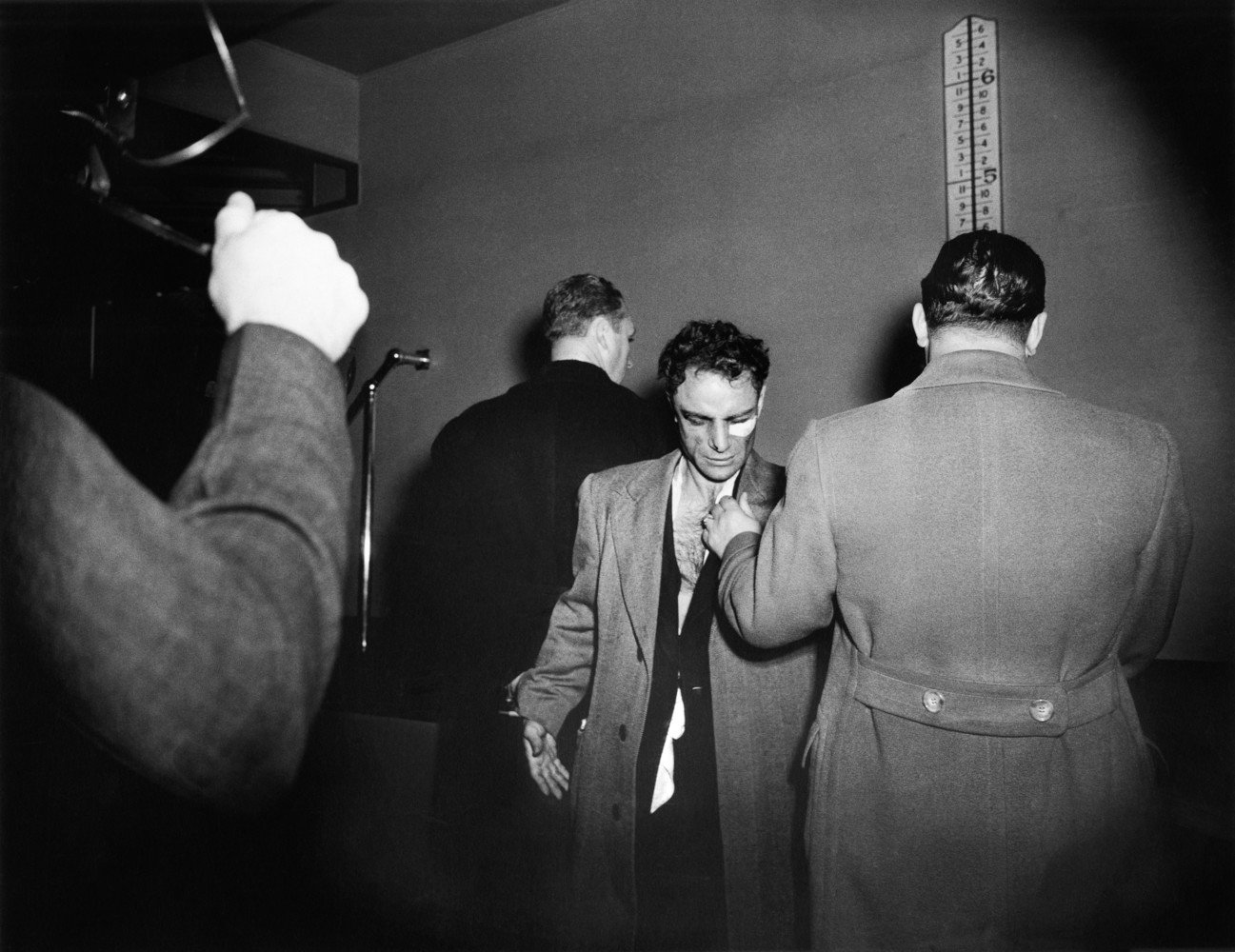

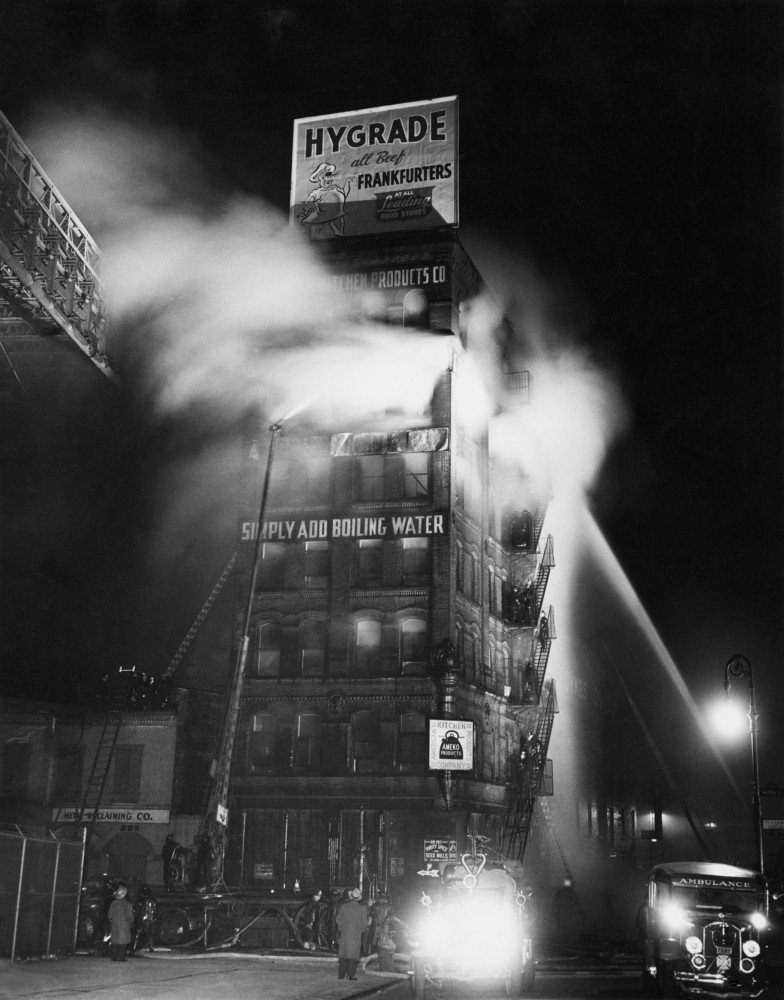

● Tension or Drama - when the empty space creates a sense of imbalance or anticipation

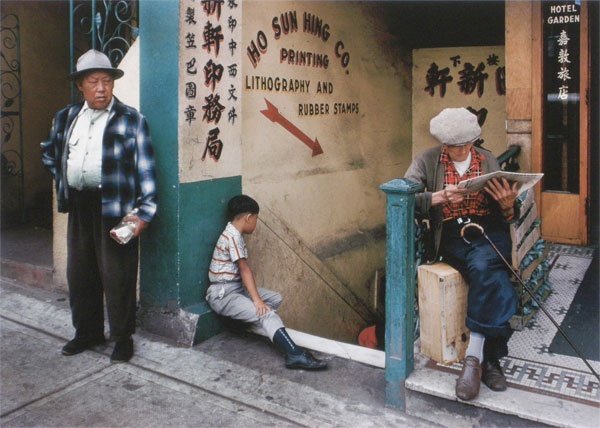

These emotional tones depend on the relationship between the subject and the surrounding space — a delicate balance that can transform a simple photo into a visually striking image.

How Negative Space Works in Composition

Every photograph is a combination of positive space (the subject) and negative space (the surrounding emptiness). The two must complement one another for the composition to work effectively.

Negative Space helps to:

● Draw attention to the subject by isolating it from distractions.

● Create balance within the frame, making the image easier to look at.

● Enhance depth and perspective especially when combined with light, colour or texture.

● Define mood and tone to give the photograph its emotional resonance.

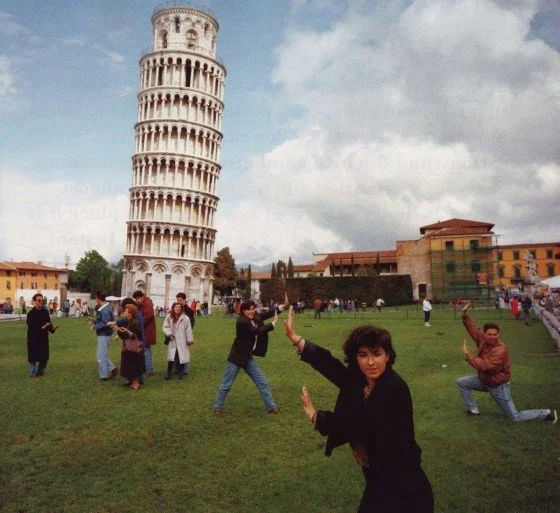

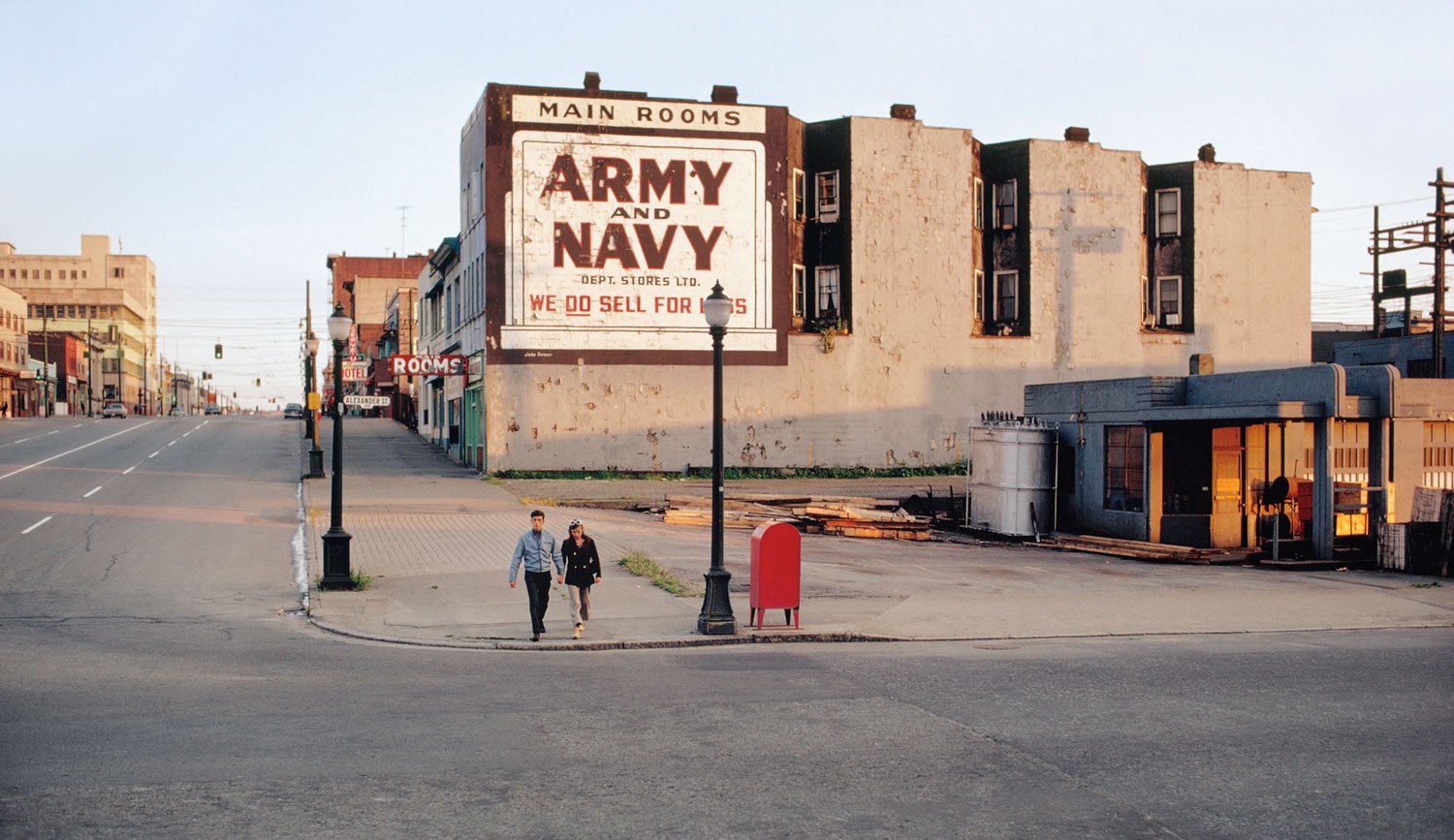

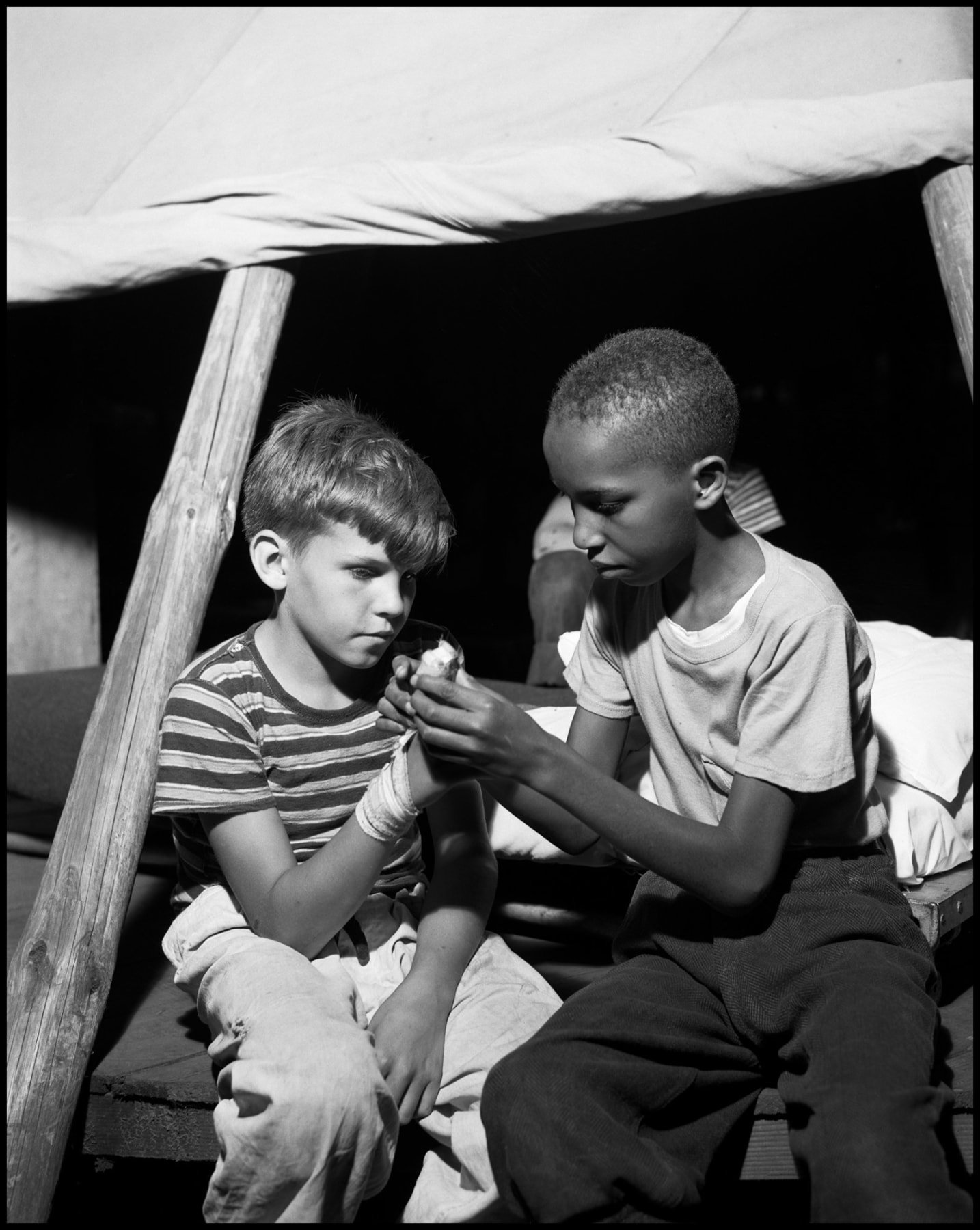

When used thoughtfully, Negative Space can turn an ordinary subject into a visually strong image. For example, a lone figure walking across an empty beach may appear small — yet the vastness around the person tells a deeper story of freedom, isolation, or peace.

Applying Negative Space Across Different Genres

Negative Space is not limited to one style, it’s a universal visual tool that works across many types of photography.

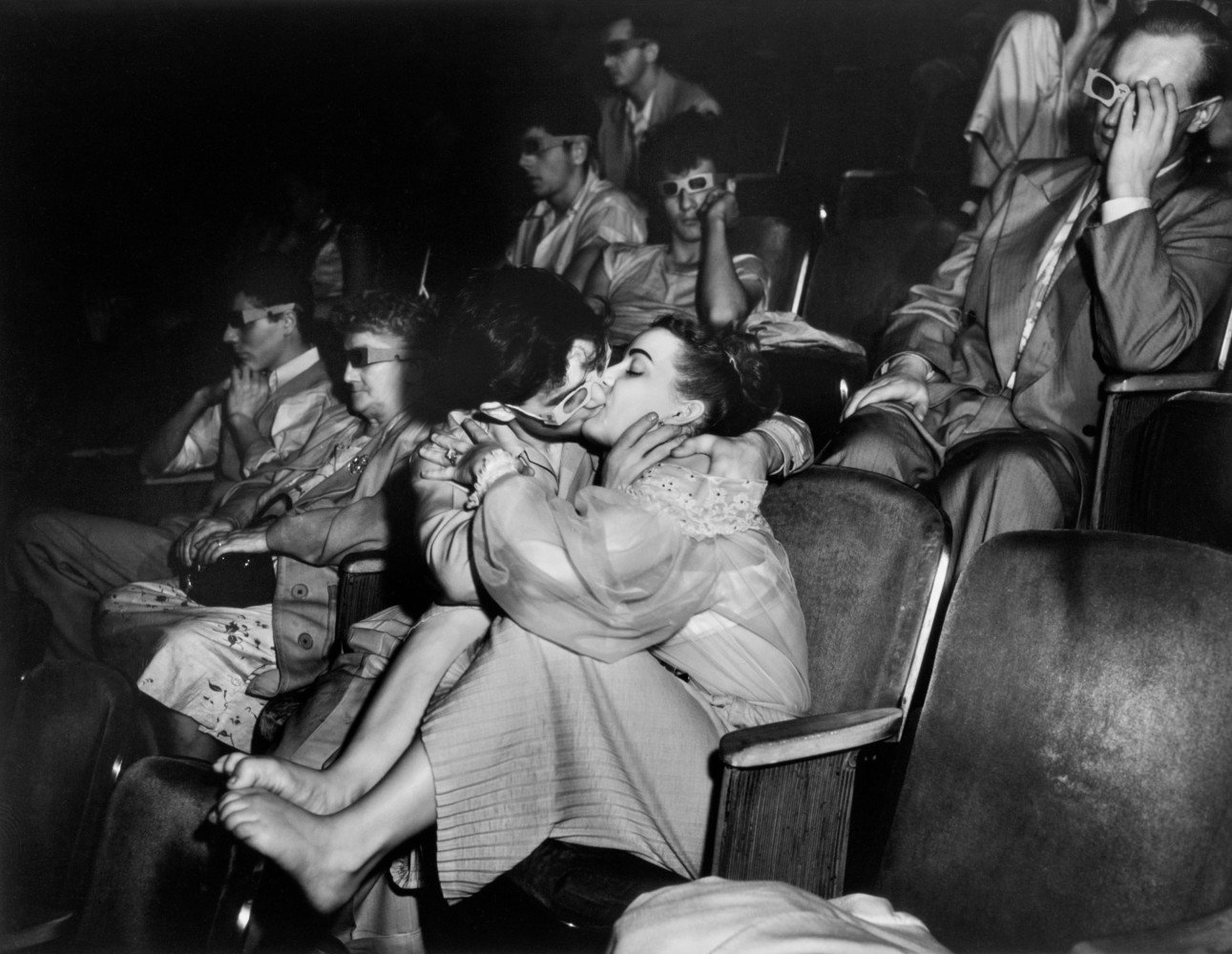

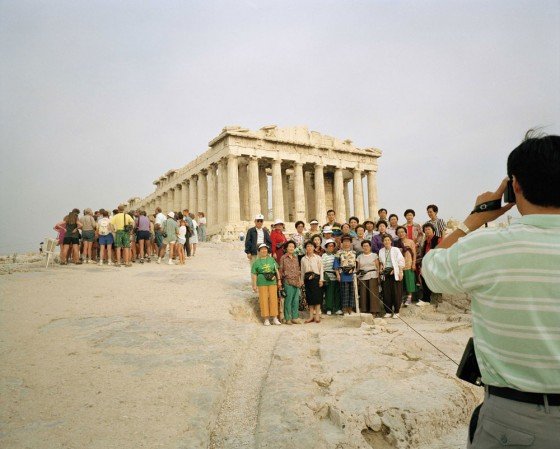

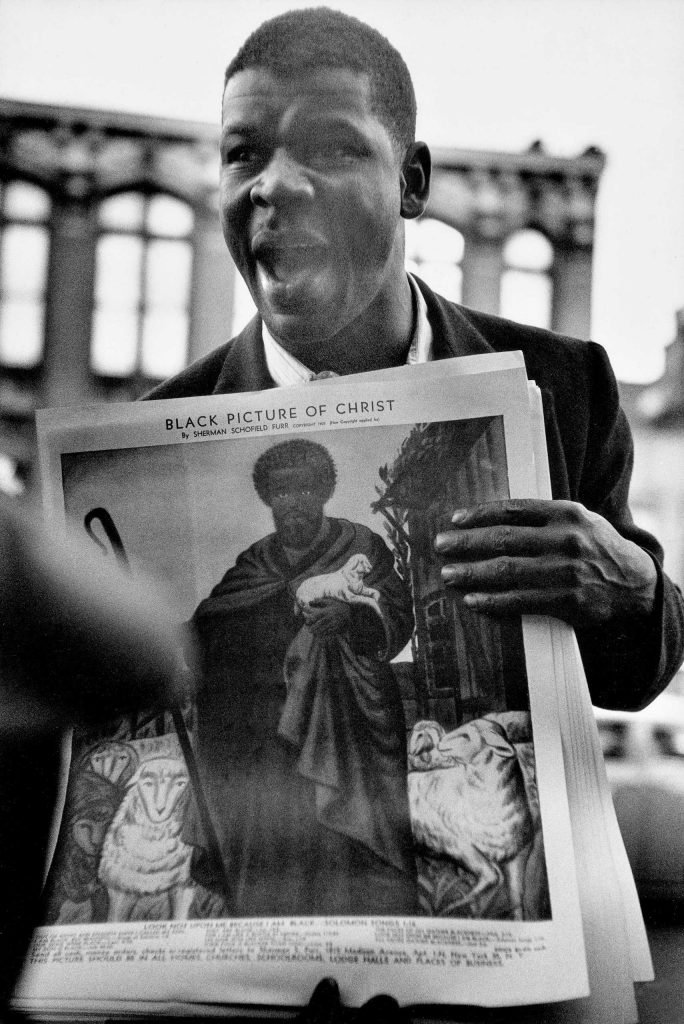

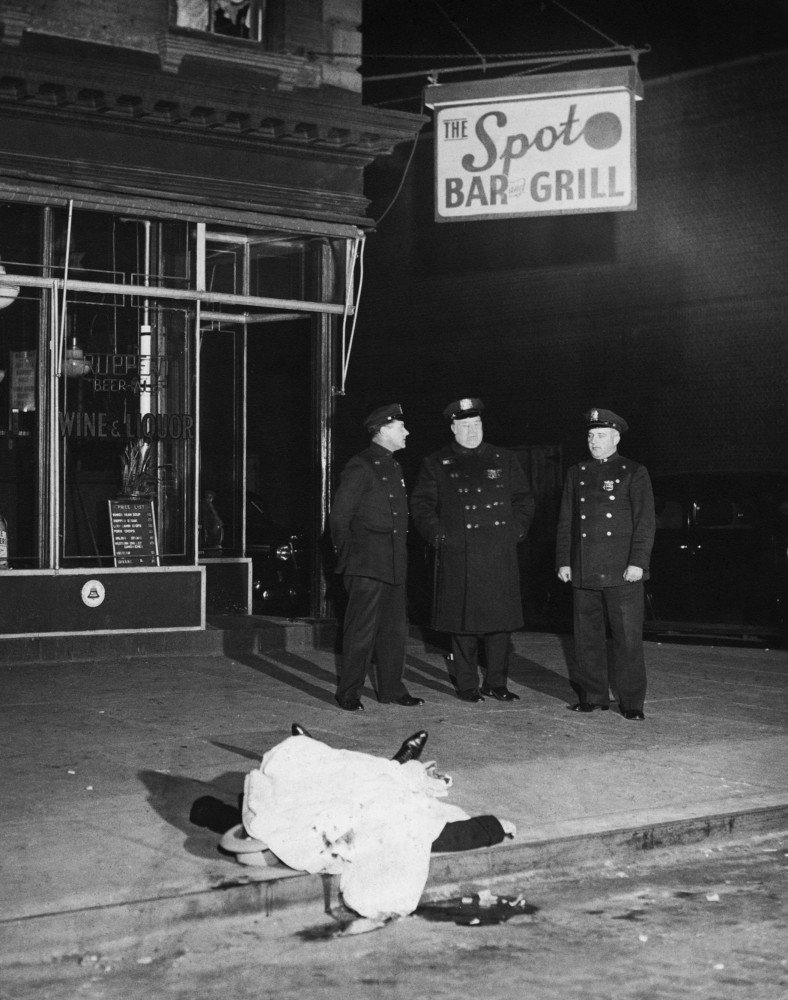

● Street Photography - In busy urban environments, Negative Space helps separate the subject from chaotic backgrounds. A clean wall or a patch of light can become a stage for your subject to stand out in.

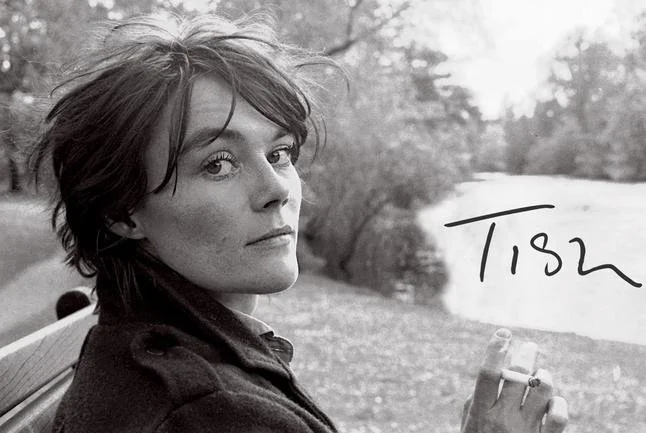

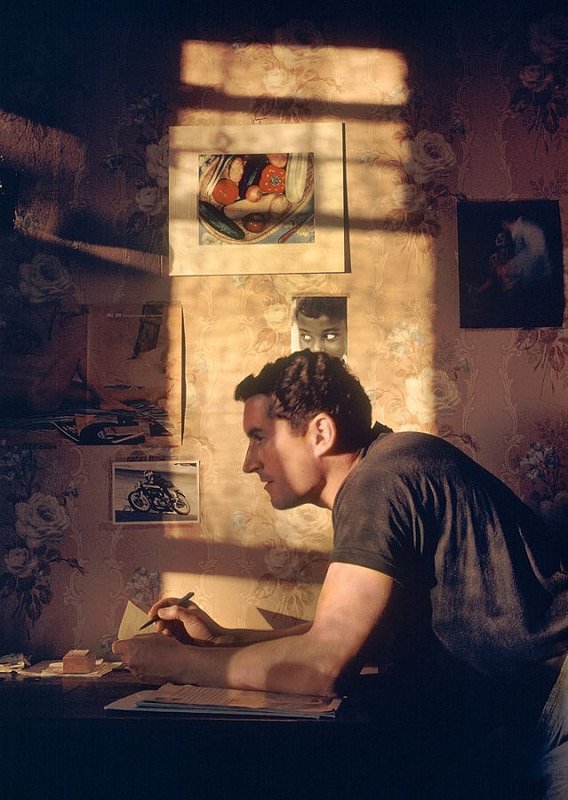

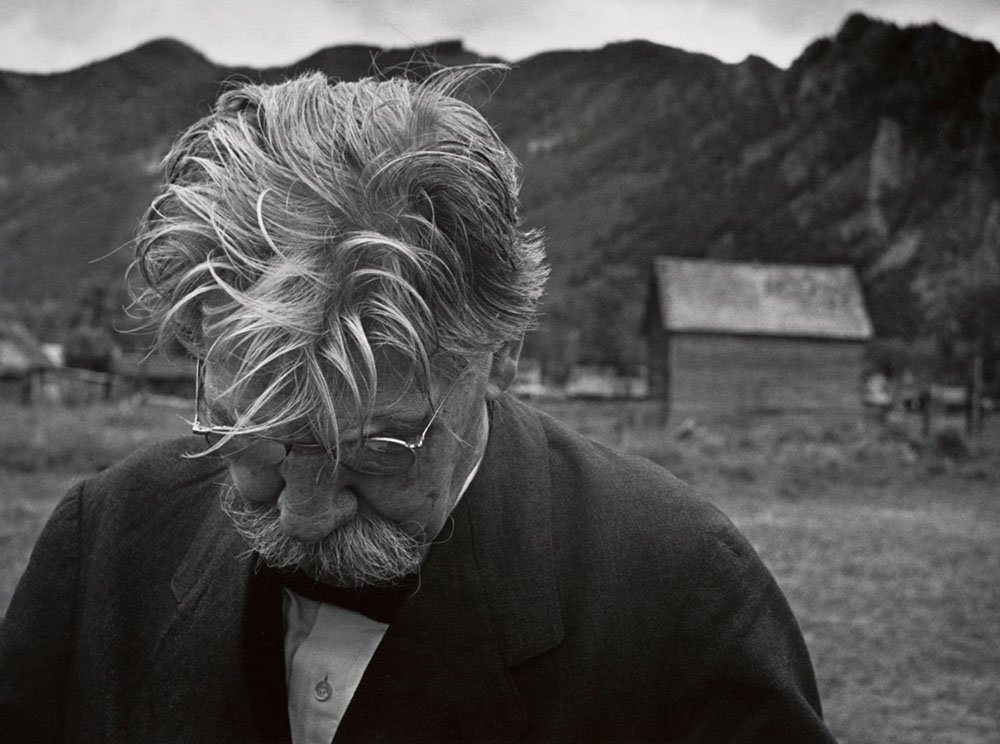

● Portraiture - Using empty backgrounds, like a plain studio wall or open landscape, can place full attention on the person’s expression and posture.

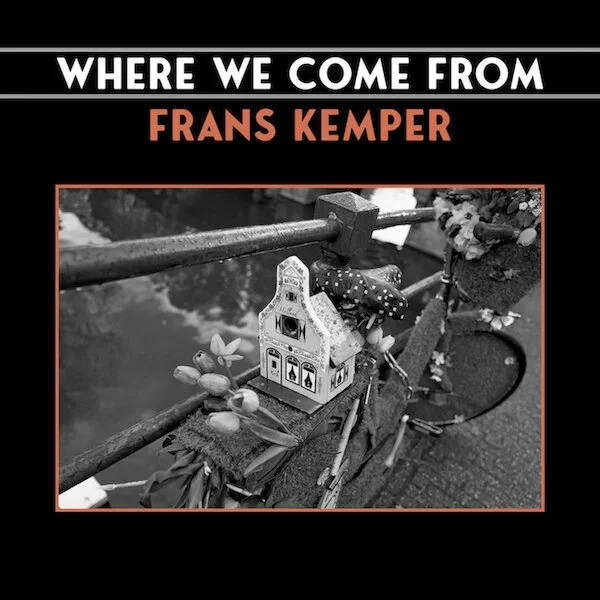

● Landscape Photography - Wide skies, open fields, and water scenarios may be used as Negative Space to create a sense of scale and vastness.

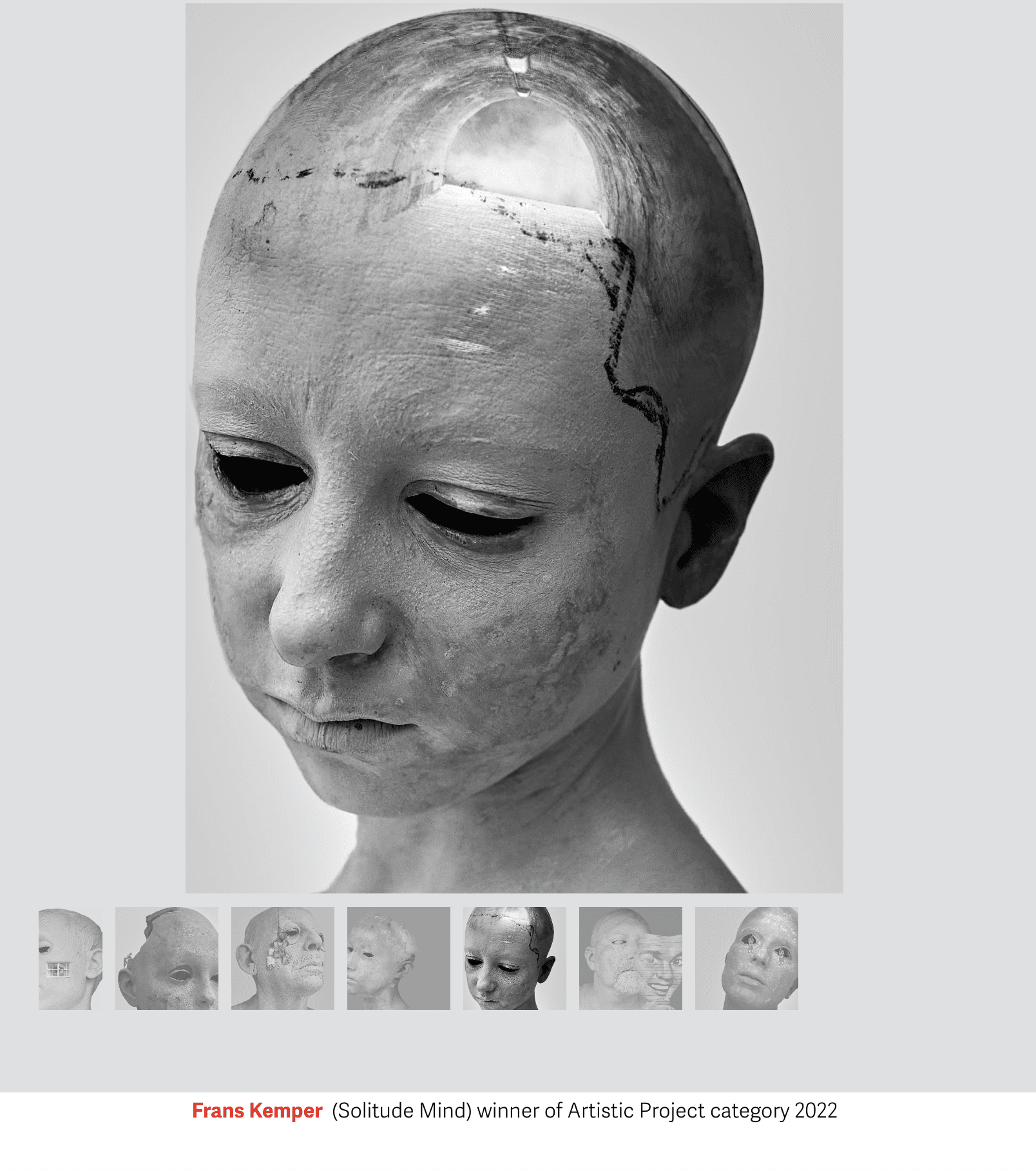

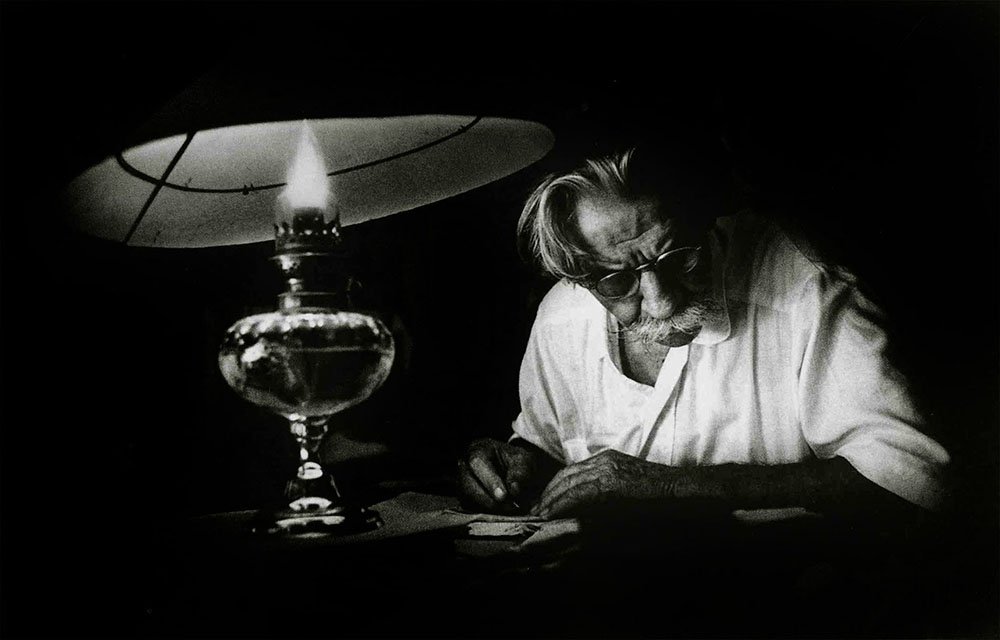

● Fine Art Photography - Here, Negative Space becomes symbolic — representing silence, stillness, and even introspection.

Each genre allows for experimentation with the same underlying idea, which resonate the same identical message - space is part of the story.

Practical Tips for Using Negative Space

Simplify the Frame - Before pressing the shutter, look out for distractions Move your position or change your framing to isolate the subject.

Use the Rule of Thirds - Place your subject off-centre and allow empty areas to occupy a significant part of the composition.

Control Depth of Field - A shallow depth of field can turn backgrounds into soft, minimal areas that act as Negative Space.

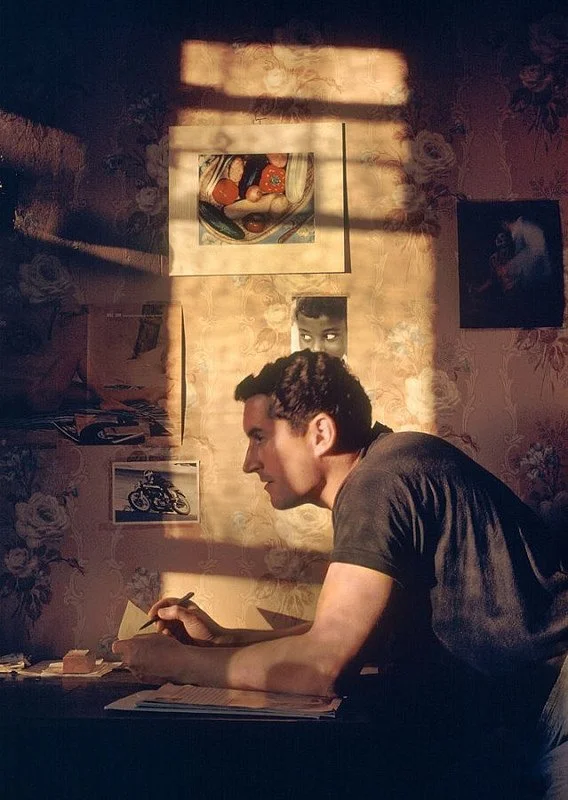

Play with Light and Contrast - Bright areas or shadows can serve as Negative Space when they complement the subject.

Experiment with Cropping - In post-processing, leave extra space around the subject to create openness or tension.

The Emotional Impact of Space

Negative Space is not just visual, it’s emotional. The use of emptiness can completely change how a photograph feels. A small subject surrounded by a vast sky may feel lonely or contemplative. On the other hand, the same emptiness can create a sense of peace and calm, inviting the viewer to pause and reflect.

In many ways, Negative Space gives photographs a voice through silence. It’s what you don’t show that often speaks the loudest.

Conclusion

Mastering the use of Negative Space takes practice and awareness. It challenges photographers to think not only about what to include but also about what to exclude. By using emptiness as an intentional design element, photographers can create images that are visually balanced, emotionally powerful, and deeply engaging.

Negative Space reminds us that photography isn’t just about subjects, it’s about how space, silence, and simplicity work together to tell a story. Once you learn to see the power of emptiness, your compositions will become cleaner, stronger, and far more expressive.

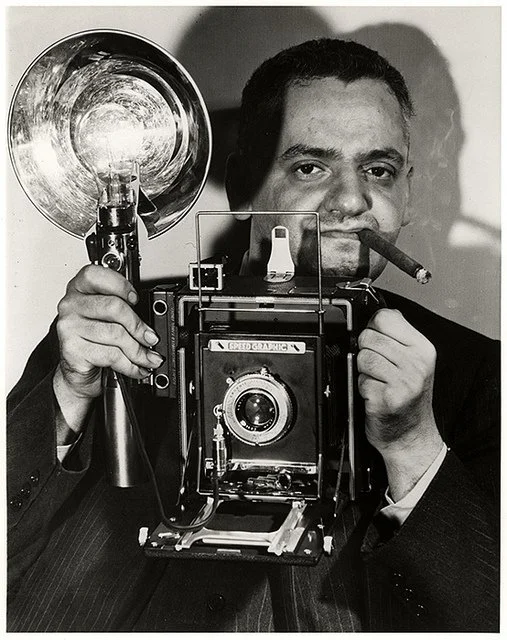

![[Afternoon crowd at Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York], July 21, 1940 © Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a815b17b7411c2497560917/1697292040616-OVAGOPPA8MH88XGWY9ZJ/weegee_2034_1993-overlay.jpg)