Gianni Berengo Gardin, who sadly passed away this August, was an important figure in photography and is known as one of Italy's best photographers. He was born in Santa Margherita Ligure in 1930, but considered Venice his true hometown, as he often said he was born in Liguria because his parents were on vacation there. His journey in photography began in the early 1950s. Since then, he has built a large collection of photographs that show the changes in Italy's landscape and society from the post-war period to today. His work covers many themes, such as social issues, everyday life, labour, architecture, and landscapes. Berengo Gardin's diverse approach gained him international fame. Many compared him to Henri Cartier-Bresson because of the beauty of his photos. However, he humbly turned down this comparison, saying he admired Cartier-Bresson but felt closer to the style of Willy Ronis.

We're trying to intrigue you here so that you can discover more about his work. It's really strange how many of his images are covered by copy, but there is no website dedicated to him in an organised way. It's the true and rare example of a photographer who thinks. He is also one of the last photographers. Today, photography is something else. And I'm not sure if I like it.

Batsceba Hardy

Gianni Berengo Gardin died at the age of 94, another of the great photographers of the 20th century, whose work propelled him into the early decades of the new millennium. To attest to the greatness of Gianni Berengo Gardin, the numbers that accompanied his work would suffice. Over 60 years of activity as a documentary photographer — “I am not an artist,” he used to say, “I document”; two million shots, almost all taken with his inseparable Leica; 220 published books; thousands of reports for major international newspapers; an enormous number of small and large photographic exhibitions across different continents.

The great photographer, “not an artist,” was actually endowed with a strong eclecticism that allowed him to explore multiple fields. From landscape photography to architecture. From street photography to portraiture and social reportage, where the ever-present light of his commitment to ordinary people, workers, and the poor was most evident.

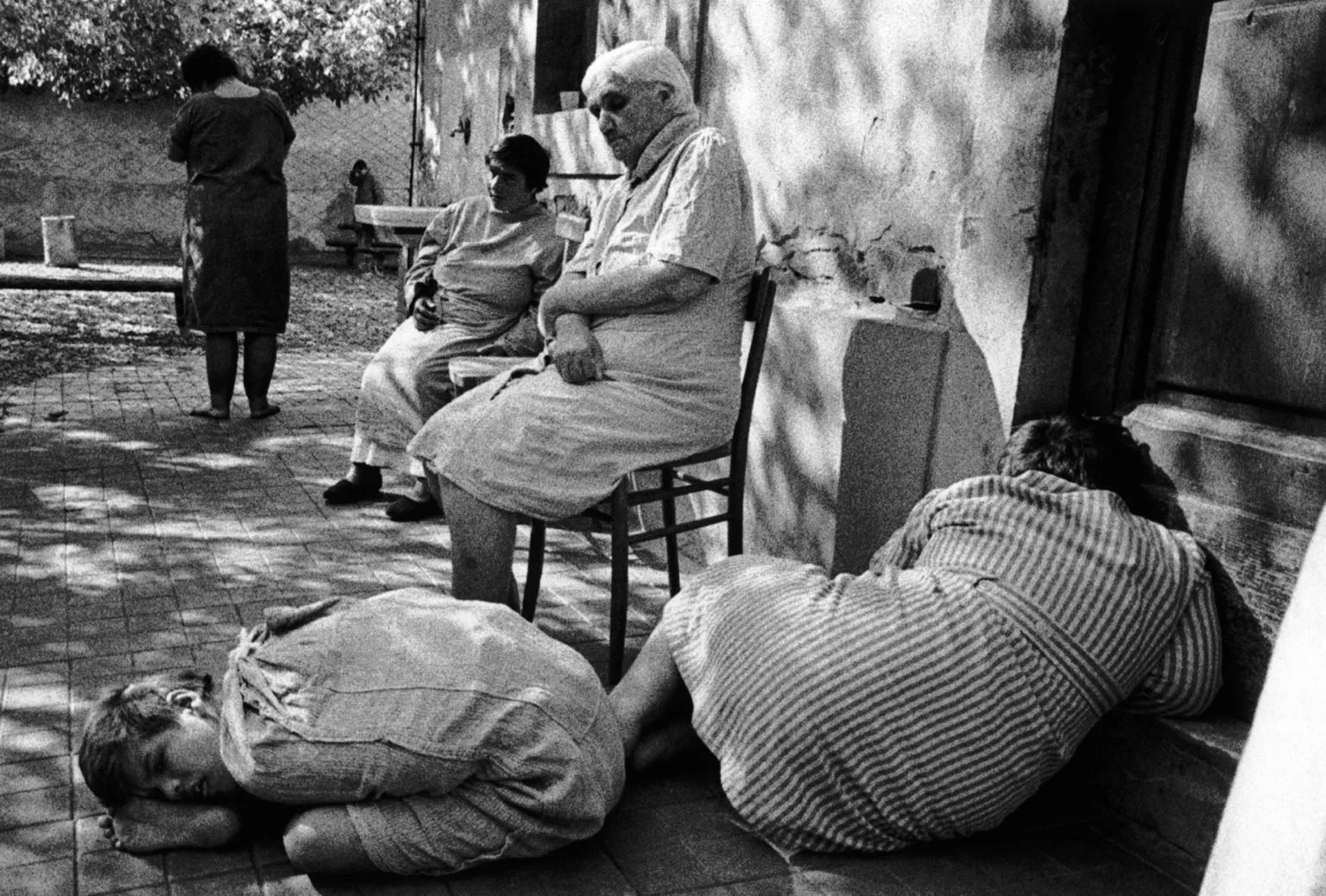

Among the photos exhibited in major European and non-European galleries, those taken in Italian mental asylums in the 1960s still cut like knives. Where the mentally ill, men and women, were confined in conditions of genuine segregation. Thanks also to Gianni Berengo Gardin’s photographs, Italian mental asylums were eventually closed for good.

Gianni Berengo Gardin, like other great photographers, refused to switch to digital and stubbornly continued to shoot with film. He insisted that every photo taken on film was a “true photo.”

Alberto M. Melis

In 1968, Franco Basaglia commissioned photographer Carla Cerati to document Italian asylums for a magazine. Uncomfortable with the task, Cerati requested Berengo Gardin to accompany her, agreeing that he could also take photographs.

They worked in four hospitals: Gorizia, Colorno, Florence, and Ferrara. Their level of access varied, with Gorizia being more open, while their visit to Florence was limited and met with resistance from the management.

Berengo Gardin captured many images, including meetings between patients, but photos featuring Basaglia were excluded to avoid the impression of paternalism.

Foot points out that the photographs from Gorizia focused more on the oppressive past rather than the unusually free conditions at the time. Before the book's release, an exhibition titled "Institutionalised Violence," supported by politician Mario Tommasini, showcased many images that would appear in *Morire di classe*.

Published by Einaudi in 1969, the book critically examines the conditions of Italian psychiatric hospitals through powerful imagery. It combines elements of photography and sociology, encouraging viewers to engage with its content. Featuring black-and-white photographs by Cerati and Gardin, the book intersperses images of walls, bodies, and straitjackets with texts by Erving Goffman, Michel Foucault, and others.

Advocating for the recovery of marginalised individuals raises ethical questions about the balance between revelation and exploitation when portraying mental illness.

In the 90s, he created the reportage *The life, despite: multiple sclerosis, diary in images*, a pivotal social communication monograph. It depicted Marigia, a 51-year-old teacher in a wheelchair due to multiple sclerosis, highlighting her daily life with visual and emotional impact. The photographer followed her in Sardinia, capturing her gestures amid fatigue and resilience. He also documented an AISM clinical centre and accessible paths on the Asiago Plateau, using his poetic gaze to show the disease's complexity and the strength of those facing it.

Synopsis In this film, beginning with Venice, BERENGO GARDIN recall past experiences as well as his many reports, such a those on the psychiatric institutes, the 1968 movement,the gypsies. All of this, always with deep respect and considering the eye, heart and mind equally important... Director: Giampiero D'Angeli Screenwriter: Alice Maxia Year: 2009 Lenght: 52 minutes Country : Italy Language: Italian; Subtitles:italiano,francais,english, espagnol Production: Luca Molducci, Giart - Visioni d’arte (Bologna, Italy) In collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna

Venezia e le grandi Navi

The reportage started two years ago as a gesture of love for Venice, a city I've long felt connected to.

I began photographing Venice in 1954, first as an amateur and then professionally from 1962. Due to my bond with the city, I couldn't ignore the threat from massive cruise ships crossing the Giudecca Canal daily. Seeing them for the first time, I was shocked, not just by their size. My amazement turned into indignation.

These ships, twice as long as St. Mark's Square and as high as the Doge's Palace, jeopardise Venice's health. They cause pollution, create waves that erode foundations, and risk accidents like the one in Genoa in 2013. If they hit historic buildings, the damage could be irreversible.

For two weeks, I woke at five to photograph the ships passing by, sometimes waiting hours, often in cold and rain. Sometimes, no ships appeared.

I knew these photos would matter. Though protests against large ships existed, I'd seen no images showing the havoc they cause.

My photos are honest, without Photoshop- if possible, I'd ban it. Sometimes I used an 80 mm telephoto lens, sometimes a 50 mm. Anyone in Venice can experience this firsthand. The ships' surreal size and black-and-white contrast draw viewers' attention.

This is a straightforward denunciation, made without commission, to expose the danger and madness of this spectacle. Photography has powerful communication, as shown by Libération, which once published a blank issue to highlight photography’s emotional impact.

My photos aim to document and provoke reflection on the reckless pursuit of profit, risking Venice's extraordinary heritage.

Venice has changed, increasingly for tourists rather than locals, but I still love it, especially from midnight to eight in the morning.

For reportage photographers, the work is over; there is no more work for them. There is work for fashion, advertising, and architecture photographers. These days, everyone makes reportage, even with a mobile phone, and therefore there's an inflation of photographs, often good ones, but the majority are very poor photos.

The ingredients for a good photograph are the content that tells something (and today's photos tell little), content that is ideally connected, even if not always necessary, with a formal value.

Culture has always been important and remains so today. With photography, you can create culture, or have fun, show things superficially, but some people use it to explore themes more deeply.

I would advise young people not to shoot randomly, as is often done today with digital cameras, but to start with a clearly defined project, aiming to convey a message and think before pressing the shutter. Nowadays, people shoot randomly; instead, they should think first and then, if appropriate, take photos—it's not always necessary to shoot. If the subject and the theme warrant it, then take the shot; otherwise, don’t shoot. In Milan, a major company that produces digital cameras ran a big advertisement saying: “Don’t think, shoot”. I tell my students the exact opposite.

Yes, I still shoot with film because I believe it is much superior to digital. Digital photography has only two advantages: immediacy (you can take a photo and send it to Delhi or Moscow in two minutes) and the ability to adjust the sensitivity (if taken in a bright place, you can lower the ISO, and vice versa).

The analogue is superior to the digital.

Especially in archives, digital archives will no longer exist. However, archives are essential, as demonstrated by this exhibition, which includes photographs from sixty years ago. A negative can always be printed even after two or three hundred years. For digital, however, you can never be sure.

Interview on the occasion of Dialoghi sull'uomo, il festival dell'antropologia del contemporaneo 2017 – Pistoia