A Socio-Anthropological Analysis of Artisanal Production in the Mediterranean Context

The artisanal production of vegetable charcoal in Serra San Bruno, Calabria, offers a significant case study for socio-anthropological analysis of local economic practices and cultural resilience. The workshop “Following the Last Charcoal Makers” (June 28, 2025), held in the Serre Regional Park, provided an opportunity to observe charcoal makers at work, documenting their practices through documentary photography. This article analyzes the phenomenon through four axes: the socio-economic system, cultural continuity, comparison with Mediterranean cultures, and the role of documentary photography as ananalytical tool.

1. Socio-Economic System

The production of vegetable charcoal in Serra San Bruno constitutes a localized economic system operating outside globalized capitalist frameworks. Approximately 20 active charcoal makers use traditional techniques to construct “scarazzi, ” domes of wood covered with earth that burn slowly for twenty days, transforming oak into charcoal. This process, rooted in sustainable forest resource management, relies on rotational cutting that preserves biodiversity (Calabria Straordinaria 2023). Socio-economically, the system reflects a circular economy model, integrating production with environmental and community contexts.

However, the marginalization of vegetable charcoal due to industrial energy sources highlights structural vulnerabilities, with declining demand and limited intergenerational knowledge transmission (Repubblica 2017). This raises questions about the sustainability of local economies in a globalized era.

2. Cultural Continuity

The practice of vegetable charcoal production in Serra San Bruno embodies cultural continuity linking the present to the pre-industrial past. Charcoal-making techniques, of Phoenician origin, represent a form of orally transmitted artisanal knowledge, embodying what anthropologists term “intangible heritage” (Lenclud 1987). Charcoal makers not only produce a material good but maintain a symbiotic relationship with the landscape, where the forest is both a resource and an identity space. This continuity is threatened by modernization, reducing the number of practitioners and risking the disruption of cultural transmission. The June 28, 2025, workshop underscored how such practices persist through collective memory and community engagement, offering a model of cultural resilience.

3. Comparison with Mediterranean Cultures

The production of vegetable charcoal in Serra San Bruno is part of a broader Mediterranean context, where similar techniques are historically and currently documented. In the Middle Ages, Andalusian and Maghrebi villages relied on vegetable charcoal for domestic and artisanal purposes (Braudel 1986). Today, comparable practices survive in regions like Morocco’s Atlas Mountains and Turkey’s Anatolia, where sustainable forest management remains central (Horden & Purcell 2000). Unlike extinct trades such as stone masonry, charcoal production retains cultural relevance, serving as a bridge between past and present. This comparison reveals a shared Mediterranean ethic of ecological adaptation and local resource valorization, contrasting with intensive production models.

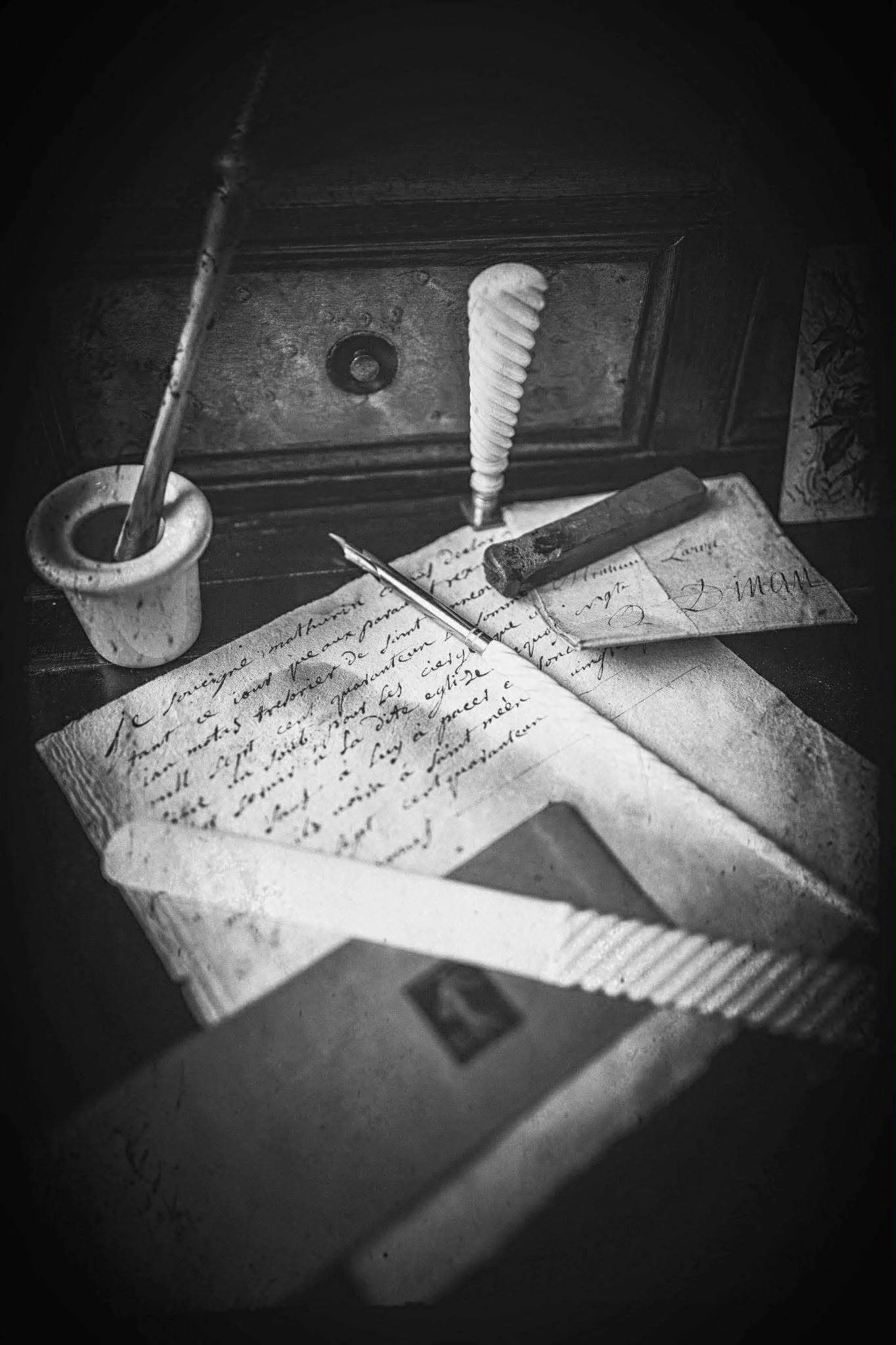

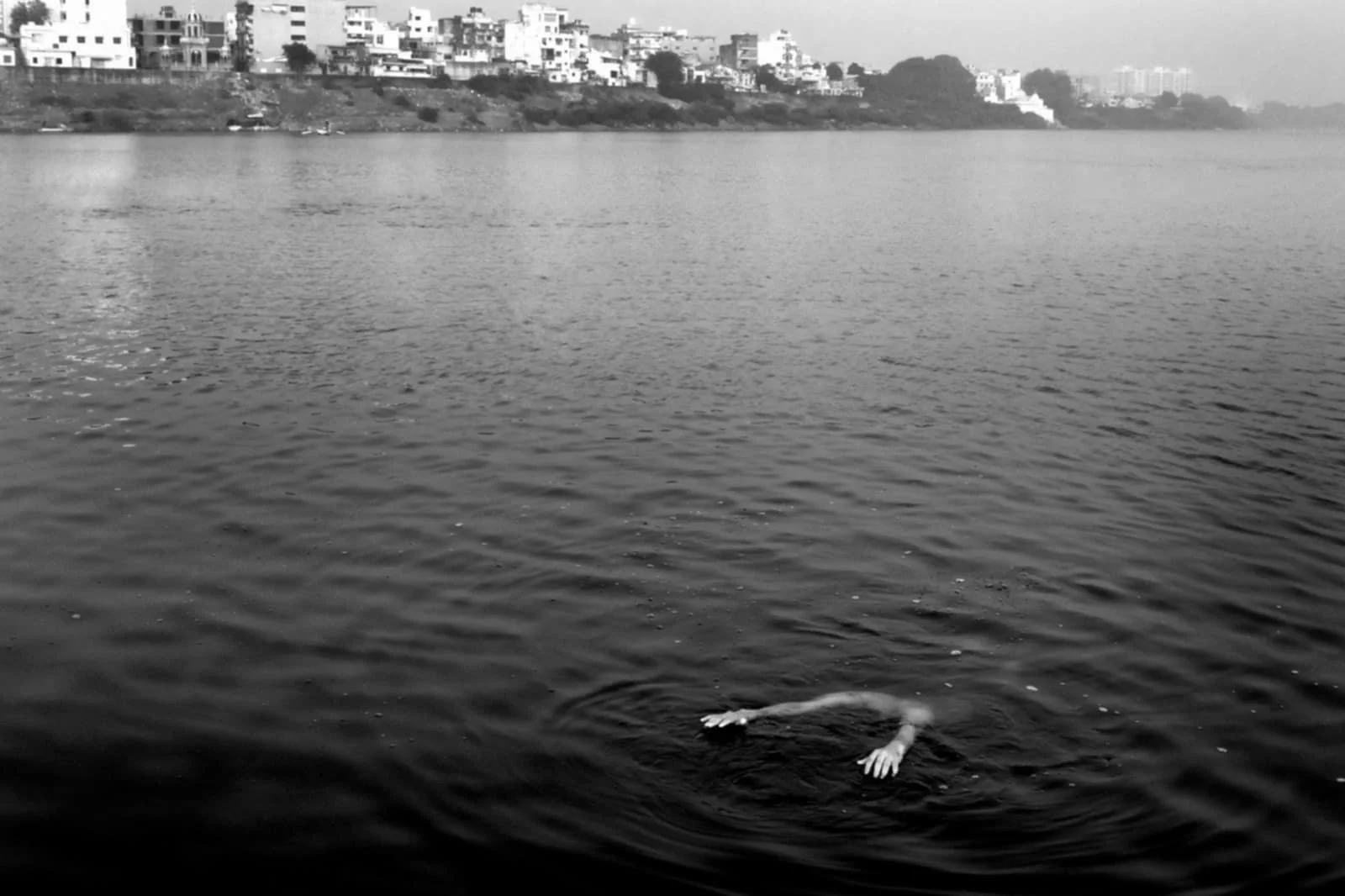

4. Value of Documentary Photography

Documentary photography, employed during the workshop, played a critical role in analyzing the phenomenon, providing a visual methodology for documenting socio-cultural dynamics. Black-and-white images captured along the Pecoraro-Lubello trail and during interactions with charcoal makers documented work processes and social exchanges, highlighting human-environment interdependence. Rooted in visual anthropology, this approach enables the analysis of cultural meanings through material and gestural details, enhancing scholarly understanding of local practices (Collier & Smyth 1986).

Conclusion

The socio-anthropological analysis of Serra San Bruno’s charcoal makers reveals a cultural and economic system that challenges dominant industrial paradigms. The continuity of traditional practices, their Mediterranean context, and the contribution of documentary photography offer insights for interdisciplinary research. Conducted through the June 28, 2025 workshop, this study underscores the importance of preserving local economies and calls for further comparative Mediterranean research. As a photographer and curator, my work aims to amplify these narratives, fostering academic dialogue on local identities and sustainability.

Biography: Ljdia Musso, born in 1985, is a photographer, educator, and curator with international training in communication, marketing, and photography, obtained in Rome, Barcelona, Marseille, Paris, and Milan. Fluent in English, French, and Spanish, she works between Catanzaro and Naples. Creator of the “Caffè Fotografici” format, she promotes free artistic events. Her projects, exhibited at Med Photo Fest 2023, explore Mediterranean culture through documentary photography, contributing to academic debates on local identities.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Nicola Romeo Arena, environmental hiking guide, who accompanied us in the Serre Regional Park to explore the Pecoraro-Lubello trail during the first part of the workshop “Following the Last Charcoal Makers” (Saturday, June 28, 2025), and to Bruno Tripodi, photographer and expert guide, who led us during the second part, engaging with the charcoal makers. Their invaluable contributions made this experience unforgettable.

References 1. Braudel, Fernand. 1986. Civilization and Empire in the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Milan: Einaudi.

2. Calabria Straordinaria. 2023. “Following the Last Charcoal Makers.” [https://calabriastraordinaria.it/eventi/sulle-tracce-degli-elli-carboniai].

3. Collier, John Jr., and Maria Smyth. 1986. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. London: Routledge.

4. Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. 2000. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Oxford: Blackwell.

5. Lenclud, Gérard. 1987. “La tradizione non è più quella di una volta.” In Antropologia e patrimonio culturale, edited by P. Clemente, 45–60. Rome: Carocci.

6. Repubblica. 2017. “The Last ‘Carvunàri’ in Resilient Calabria.” [https://www.repubblica.it/r2-fotorep/2017/03/28/news/ ] gli ultimi carvunari nella calabria che resiste-161594521/].