The river still belongs to them

by Delfim Correlo

Doubt. The word was there, written on a small square sticker, attached to the handrail of the D Luís I bridge’s lower deck. I noticed this when I photographed him: he balanced on the iron railing like an experienced juggler, focused, without hesitation, showing experience.

He came near to his friends who were preparing to jump into the river and were already outside; hands and arms intertwined in that X-shaped iron lattice with over 130 years old. In front of them, more than 50 feet down, the river that, shining in the sun, looks like gold. They show no fear. They smile at us while we pass on the bridge, "give me one euro so I can jump into the river" and closing the hand "I hold it here when I jump, I don't lose it". "Give it to me and I'll keep it in my shoe"- said a second boy - "in the end we share". I know it's true because I saw it more than once. They do it in groups of 3 or 4 and, in the end, they get together and count the money they made, before and after the jump.

They are near to the north pillar of the D Luís bridge - a bridge in metallic structure built between the years 1881 and 1888 - in its lower deck, which connects the riverside areas of Porto and Gaia.

I remembered my son. The youngest would be how old? 12, 13 years? The older ones are between 16 and 18 years old… but they usually jump next to the South pillar. There it is more difficult. The access to the margin forces them to climb a stone escarpment that supports the pillar itself and that gives access to a small square, which is at the level of the bridge deck, and where tourists gather to admire its jumps.

Here, on the north side, when they jump, they will swim to the margin: a stone ramp that, going around the pillar that supports the bridge, goes up to the riverside where some of their family members sell handicrafts, souvenirs from Porto, in makeshift stalls (one table to display the artefacts and a sun patch). The business has never been easy, but this year, with this "covid thing", is getting worse.

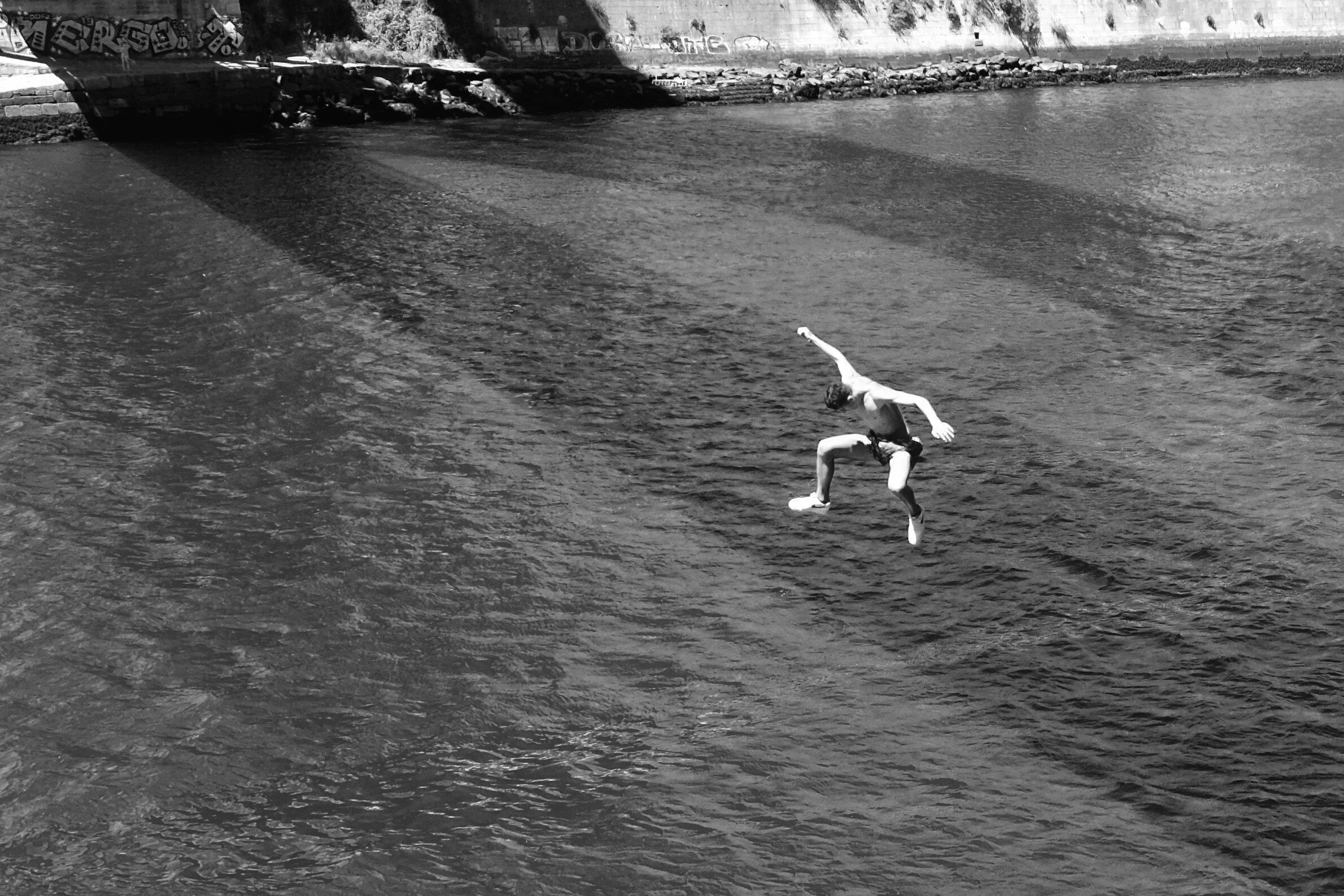

They don't jump yet. "Not now. The river still pulls”. And they wait a little longer. They laugh. Three guys and a girl. And suddenly, the first one jumps. He seems to fly. One by one, carefully examining the river they know so well, they jump. They take breaks (“the river still pulls”) and I notice that, after the jump, they don't swim right up to the riverside; they wait down there, for the others, and only when they are all safe they swim to the safety of the stone ramp that goes down to the river.

Along the riverside area of Porto, we see tourists scattered everywhere, some taking a break and enjoying the sun, sitting on the restaurant terraces overlooking the river and the south bank. Being outdoors - whether having lunch or a drink - you don't see many masks, giving this whole picture a strange feeling of fragile normality.

Several cruise boats, which provide routes on the Douro River, are anchored here and there are already lines of people to buy their place. And it is here, next to these anchorages that we see them again: the river's boys. Here the jumps are neither so high nor dangerous; here they don’t receive one euro for doing it. They are just children who live around here, who love their river and like to bathe in it, the strokes are hugs they give to an old friend and the jumps into the water are repeated dives… their parents did the same once. This is where they learn to swim and get to know their river: "o Douro".

There are stories that are told: the man who, trying to commit suicide, threw himself off the top board, about 200 feet. He was saved by a woman, a saleswoman, used to the river since she was a child who launched herself into the water. Or the young American couple; he decided to imitate the boys he just saw and jumped off the lower deck ... but it was not his river.

Here everyone knows them. We see news in the newspapers and on TV calling them “the boys of the river”, saying they become a “tourist attraction” and, a few years ago, a Spanish director even made a short film about them and with them.

I hear whistles in the distance; the older ones must already be on the south side, over the railing of the bridge. One will be on the small square asking for one euro for the friend who will jump and take a dip ... ”5 euros left”… “3 euros left”… At fifteen / twenty euros he shouts to the guy on the bridge: “You can jump!”. And he jumps, swimming to the cliff and making his way through the rocks to the top. A friend will come to him with a towel and give him a hat for, in a second round, the boy who has just jumped to collect some more money. You can see that he trembles and if we ask him “Why did you do it?” he will probably answer with an honest look “for the money” and, kindly, he will say “Thank you”. Then they will rest against the huge stone wall of the pillar. And they will start again, until the summer ends.

I know the question because I asked it myself too: is this legal? The official answer appears to be "it is not illegal".

There’s a second question: “Is it fair?”.

I leave the river behind, I go into its steep streets, where several restored buildings gave rise to properties for local accommodation, hotels, restaurants… an economic model, post-crisis, based almost entirely on tourism… centrifugation… looking up I see cranes in the sky. They claim their space, they are made of steel too, like the bridge from which they jump.

The jumps from the bridge to Douro. Perhaps it is a statement: the river still belongs to them.